Part of the fun for any post-apocalyptic setting is to see how far the worlds go in reshaping civilization. Many aspects we take for granted, from food to clothing to even pre-war relics of civilization, become flipped into a macabre version of what could be. Rich settings like Fallout, S.T.A.L.K.E.R, and Wasteland have shown us what the world can be after civilization ends and how life finds a way beyond what we would expect.

What makes such settings fun, at least for video games, is how imaginative developers can get in formulating their world. The post-apocalypse is always, in some form, about survival. Thriving in inhospitable wastelands in a constant struggle to live, often they are ripe with conflict and adversity for players to overcome. This in and of itself is done through in-game lore mostly, tangentially tied to simple mechanics such as food and water consumption or severe weight limits.

Sometimes though, games can tie their setting into much more meaningful ways. Little touches such as gaining bottlecaps for opening Nuka-Colas in Fallout come to mind as an example of this done well, providing an in-universe reason to hoard Nuka-Cola outside of it healing the player. P

Perhaps though, one of the best implementations of uniting gameplay with world-building comes from the Metro series, and specifically their primary currency being the only protection they have: bullets.

The Metro series, starting with Metro 2033, is a post-apocalyptic first-person shooter based on the novel of the same name by author Dimitry Glukhovsky, first published for free in 2002 and commercially in 2005. The novel talks about survivors of nuclear war, living underground in Russia’s metro system, scraping together a living against mutated animals and various factions.

The game, which follows parts of the novel, would flesh out Glukhovsky’s world even further, finding clever ways to bring elements touched upon in the books into the game world. This does make sense considering Glukhovsky has had involvement with the writing and direction of the Metro series, including writing up a brand new story for the upcoming sequel Metro: Exodus.

It is the claustrophobic feel of the rusted, decaying tunnels, the crowded slums of huddled masses and the freakish enemies encountered in the dark. Glukhovsky, and in turn the Metro series, is excellent at setting the mood of the world for it's players. Perhaps the most lasting impression is how scarce supplies are in conjunction with this world, as actively finding ammunition is difficult and the choice of what to do with it is hammered further through its status as a currency.

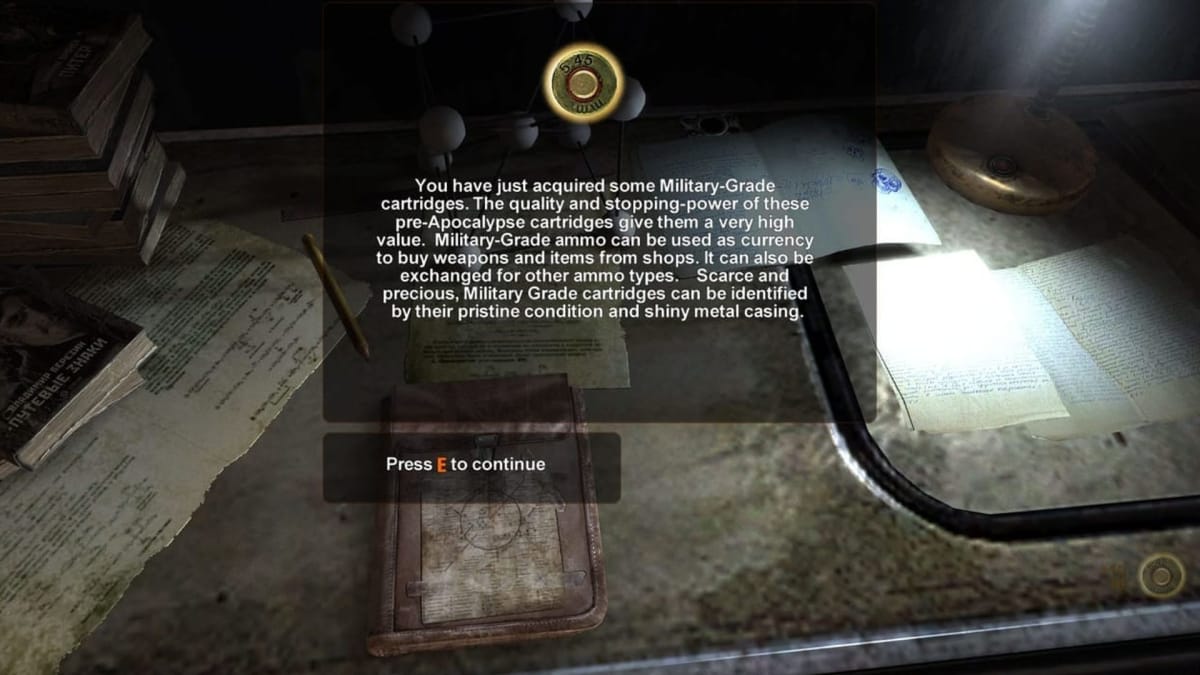

Specifically, it is Soviet 5.45x39mm military grade rounds, or MGR, that serve as the primary currency. Part of the reason why is due to their scarcity despite being a relatively common ammunition type. Historically, 5.45x39mm rounds were used for popular Soviet-era carbines, most notably the Avtomat Kalashnikova Model 1974. The AK-74 was a popular, widely used weapon in Soviet-era Russia, and later sold in surplus around the world due to the reputation of being a reliable assault rifle for military use.

In the Metro series, with technology pushed back due to nuclear war, pre-war military grade ammunition is rare. That scarcity of MGR’s, along with the fact that making counterfeit bullets is extremely difficult, sees it becoming the de-facto currency of the metro tunnels, to the point where exchange rates with other pre-war and even actual handcrafted bullets are set up to keep the economy flowing.

Bullets are used basically for all forms of amenities in the Metro books, including food, fuel, and medical supplies. For the Metro games, they serve as the primary currency for purchasing new weapons, medkits, grenades and in Metro 2033 Redux, weapon attachments.

The Metro games also give players access to a finite amount of MGRs in a single playthrough. In total, 1,391 MGRs can be found in clips and hidden caches in Metro 2033, with any extra rounds earned from weapon vendors for selling old equipment. Players are also not even guaranteed the full amount, as most of that total is derived from the highest possible outcomes from random MGR clip tables, meaning players will likely encounter less rounds in a single playthrough. While Metro: Last Light added more MGRs to find, including starting the game with over 100 rounds, in-game their relative rarity makes them an important, sometimes hard-fought reward.

Considering the nature of the game, this puts players in a tough position on what to use their rounds for as well. The games do give players other options, including other bullets which can be exchanged for MGR’s, and “dirty rounds” – the common form of MGR rounds that is not used as currency.

Dirty rounds are homemade bullets, often using inferior materials to craft them. Due to this, they lack a lot of the stopping power that would help in taking down tougher enemies when compared to the pre-war MGRs. This can lead to situations where players may be down to using only their MGRs, either as a last resort or to kill a boss character, all the while literally “shooting money” away.

There is a point of no return in both games, where you will no longer encounter any shops to use your MGRs. While this can be seen as a flaw in the games overall design, it doesn’t really take away from the real selling point of the mechanic’ the general atmosphere of the world. The Metro games are not an easy experience, and are designed to be tough on the player.

Between mutated creatures, maze-like corridors filled with radiation, an inhospitable surface world, and limited lighting and fuel, the temptation is always there to make your time traversing the tunnels easier by shooting your money away.

It is a temptation that fits perfectly with the games overall tone. Metro is a much darker, more realistic take on post-apocalyptic set pieces. The world is survival of the fittest, where planning ahead and a bit of luck can guarantee survival more than brute force. As a first-person shooter, it is a slower pace that savors its world-building, much like Glukhovsky’s books did before it, and as a game it seamlessly blends unique mechanics into the in-universe lore.

Lastly, it provides the game with a rudimentary choice and consequences system to grapple with. Blasting through enemies with the high-quality MGRs are always an option if you can afford it, but is it worth the cost? That is the type of enriching game experience the Metro series gives its players; a sense of ominous anticipation of what is around every dark tunnel that will force you to give up your very means of survival, just to save your life.

In this way, MGRs in the Metro series stand out as one of the best implementations of in-game lore tied to in-game mechanics. It not only helps Metro stand out amongst its peers, it also sets the overall tone of the game’s world and its challenge to the player. It provides conflict and consequence for the player's actions, which can be directly punishing if they are not careful, all the while being a tangible example of how dangerous the world of Metro really is.

This post was originally published in 2019 as part of our Bullet Points series. It's been republished to have better formatting and images.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net