For the past several weeks, I have been playing through NieR: Replicant ver.1.22474487139, a remake of the 2010 action RPG cult hit, NieR. A lot has been discussed regarding its technical presentation, its relationship with its 2017 sequel NieR: Automata, as well as what it means for the series going forward. But the changes made in this remake are perplexingly mundane but quietly profound in a way that makes me wonder just how much of them were meant to be examined critically and how much if it was more elaborate subterfuge by director Yoko Taro.

First, a very brief and heavily abridged summary of the 2010 original game and the remake's interesting history. At a very basic level, the original NieR is an action RPG where the main hero is tasked with saving a family member of theirs from a deadly disease known as the Black Scrawl, which has wiped out most of humanity. It is only after discovering a talking magical book named Grimoire Weiss that the hero sets out on a journey to defeat a villain known as the Shadowlord, who commands an army of monsters called shades to kill and terrorize local villages. While on this journey, the group is joined by a foul-mouthed warrior named Kaine and a kind-hearted skeletal wizard named Emil.

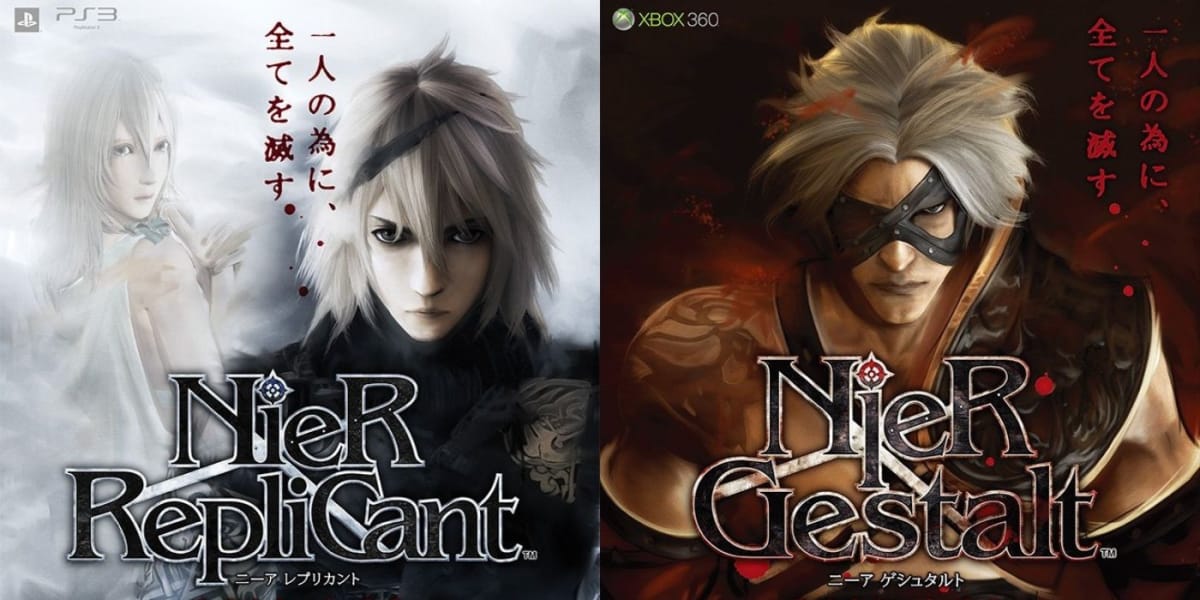

Curiously, there were two different versions of NieR that were released in different territories. The first most people in the West played has been labeled NieR: Gestalt, which makes the hero an older man with bulging muscles and a gravely voice; the family member he's saving is referred to as his daughter. In addition, there were altered minor story elements that mostly toned down more esoteric or potentially off-putting subject matter to a general audience. This version was released in North America, Europe, and the PAL regions, the implied logic being that a more gruff and overtly masculine protagonist and fewer weird story elements would help get players normally turned off by traditional JRPG tropes and cliches to check it out. In a way, it was ahead of its time when it came to the videogame cliche of the father protagonist that would become popular in the wake of The Last of Us and God of War.

Alternatively, if you were in Japan, you were also treated to NieR: Replicant. This version is identical except the main hero is an anime teenage pretty boy, and the family member affected with the fatal disease is his sister. It is also the more authentic version of events since the text and character beats are unchanged. These beats include revealing Kaine as an intersex woman, the origins of which are tied to several major twists near the end of the story involving robot duplicates and soul-transference (no really), and Emil being gay and in romantic love with the main protagonist. This version was never released outside of Japan until the 2021 remake.

And if this was any other action RPG, those details would be tertiary at best. But NieR Replicant was directed by Yoko Taro, the eccentric director who seems to treat the trappings of a genre more as a means of pulling the rug out from under players rather than engage directly. This is the same director that got Platinum Games, a studio renowned for extremely stylized and satisfying hack-and-slash combat, and had them make a game where the player figures out the countless mooks they were slicing through with gorgeous acrobatic skill had families, wants, and desires that were cut short for cheap spectacle.

It's an attitude that has branded Yoko Taro's games as nihilistic, treating its own players with disdain. On the surface, NieR Replicant is no different. This is an RPG full of side quests that do nothing other than waste your time with busywork, or highlight characters that learn nothing from the hero's input or perspective. The game has multiple endings but forces you to repeat entire swaths of content over and over again to the point of numbing any satisfaction in the core combat. Finally, there's a prevailing atmosphere of post-trauma anxiety where society is constantly on the edge of collapsing and everyone is desperately clinging to their own wants before everything breaks down. These games can't help but be seen as outwardly antagonistic towards its very audience with these elements in play.

Taken on its own, this bleak perspective sours and hollows out the small addition of the remake's Episode Mermaid chapter. This is essentially a filler mission where several minor characters you run into are murdered by a monster taking the form of a little girl, then dramatized through a dark retelling of Hans Christian Anderson's The Little Mermaid. It's a sad and melodramatic addition that adds maybe two additional hours of content all together. Even when given a new set piece of fighting a large kraken monster with stylish combat, this persistent feeling of “why even bother” permeates the air.

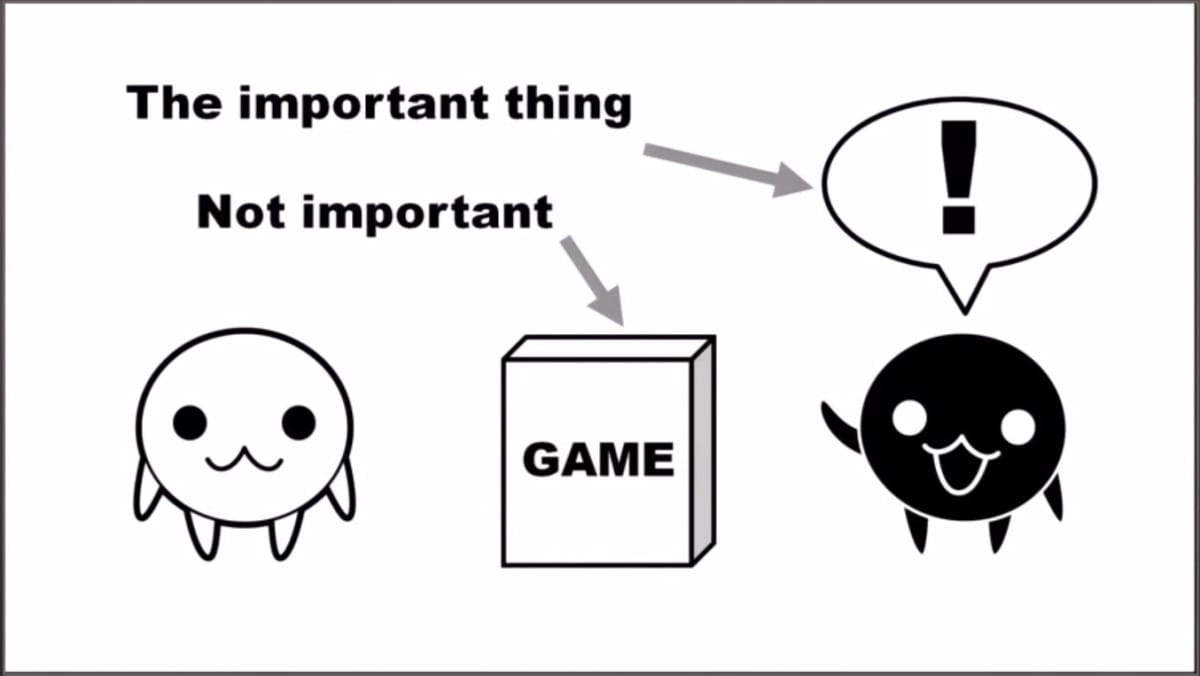

But this design philosophy is intentional. Speaking in a GDC talk in 2014, Yoko Taro mentions that the core gameplay loop: the combat, the side missions, the weapons and magic spells, etc., are not the focus of his games, but how the characters and players are affected by the very turns in the story. Taken within this context, the restoration of queer coding to Kaine and Emil turns them into vastly sympathetic and even aspirational characters. Despite Kaine already being a subversion of the warrior woman in lingerie stereotype—here framed as an inhumane monster, she still comforts characters seen as different. It shows a tenderness and compassion that rings more true when contrasted with the world's bleakness—that is, as long as you ignore a certain tone-deaf achievement. Emil has an even more passionate lift in this regard. He starts as an innocent child locked away from the world for being different, and he ends up becoming even more alien as the story progresses. Yet when he expresses feelings for the main hero, it is not grounds for derision or even used for a joke.

But this case of emotional subtext taking over the ludic text is heard the loudest with the main story and the fate of the main hero. As NieR Replicant progresses, the main hero slowly changes from a naive young boy into an embittered and violent adult, his ideals crumbling into pure bloodlust. This is coupled with several major twists in the game's plot involving the true nature of the shades, the Shadowlord, and even acts of murder committed by the hero. This culminates in the final ending of the original game where the player must sacrifice themselves to save the world. Not just the main hero deleting their very existence from the world to ensure the safety of his friends and family, but the player willingly erasing their save data to ensure the world recovers from their destructive actions. The melodramatic and defeatist idea of “you shouldn't have even gotten involved” is played out in sincere bittersweet bombast.

But keeping with Yoko Taro's eclectic style of emotional honesty overriding the text, this merely sets the stage of the remake's brand new ending. This is the part of the game where you play as Kaine, and where it seems NieR Replicant diverges into unapologetic, indulgent fan service. This is the ending where Kaine encounters major locations and central plot points from NieR Automata, a sequel set thousands of years in the future, and is thrown into a virtual simulation where she goes into a boss rush gauntlet. On its face, it reads like a victory lap with the UI and visual aesthetic swapped around.

Then the ending comes with a message so clear and so blunt that it hurts. Kaine pulls the main hero back into existence, restoring your save data in the process, while yelling about how selfish it was for you to do such a sacrifice. Taking into account that NieR Automata's events begin once the world of NieR Replicant crumbles into dust, the final ending can't help but be read as defiant and tragic. You have experienced everything in the game at this point; there is nothing to do now but continue to the sequel where everything you did has long been forgotten; your save data is effectively worthless at this point. But the final shot of the game, of Kaine holding onto her newly restored friend as the world continues to crumble, shows where the heart is all the same. Everything is going to end, every mistake was made, but at least she has the people she cares about with her when it happens.

NieR Replicant ver 1.22 is the kind of game that only Yoko Taro could get away with. It's a remake of the Japanese-only version of a game released 11 years ago that started by saying nothing the hero did mattered but now states that the journey was still worth it. Despite adding in new material and new content, the real powerful moments didn't come from the three hours of brand new gameplay and fan service, but from the character beats given new light in response to this new material. Much like Yoko Taro's other games, despite me feeling badgered and belittled by the gameplay, I suffer it gladly to see the journey it's wrapped around.

TechRaptor covered NieR: Replicant ver.1.22474487139 on PlayStation 4 with a copy provided by the publisher. The game is also available on Xbox One and PC.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net