“I am not Link, but I do know him! Even after 18 years, the Legend of Zelda never stops changing and this game is no different. We are now taking you to a world where Link has grown up–a world where he will act different and look different. In order to grow, Link must not stand still and neither will I.”

– Shigeru Miyamoto discussing The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess

It is hard to put into words the cultural impact a character like Link has on people. Immortalized in the highly successful Legend of Zelda series, Link as the timeless, sword-wielding, green-tunic wearing warrior is perhaps the most widely recognized mascot in the world of videogames next to fellow Nintendo stalwart Mario. Link is arguably the benchmark for excellence for an entire generation of adventure fans since his debut 30 years ago. Now, with over nineteen different incarnations of the eponymous hero, Link has already secured his position as one of the greatest video game characters in the world.

But the next question is why? Why is Link so memorable to us, despite the fact he has barely uttered a word in 30 years of existence? What is the allure, the appeal of a character that has gone through so many incarnations? Of course impressive production values of each Zelda game help his case, as does the near timeless, adventure-style gameplay, but whenever someone puts forth an idea for the best video game character in the world, Link is often at the top with a select few individuals.

A sort of anomaly because he is so different than other gaming characters, to answer this question of why, we need to look at what Link represents in the Zelda universe over what he actually is. As a character, Link personifies not an individual on a specific quest, but rather a timeless hero of mythical legend that can encompass all forms of storytelling to the player. Add to this the fact that Link is also a controllable protagonist, the games exemplify the power of interactivity of a storyline that is near unparalleled in its form today.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VE2Dc1sx71U Each game, bar a few official sequels, feature a different Link in the official canon, which has been a conscious decision of design to create a mythical structure surrounding Link. A myth, in its barest form, is a story that almost everyone knows, but it is steeped into a world’s tradition. Stories such as Jason and the Argonauts, Heracles and the Twelve Labors, and the Epic of Gilgamesh in ancient mythologies are prime examples of this. They follow a pattern to them because the story has a set pattern: a hero rises through adversity by using different skills, help from allies, their wits and their courage, overcoming obstacles and winning the day when all hope seems lost.

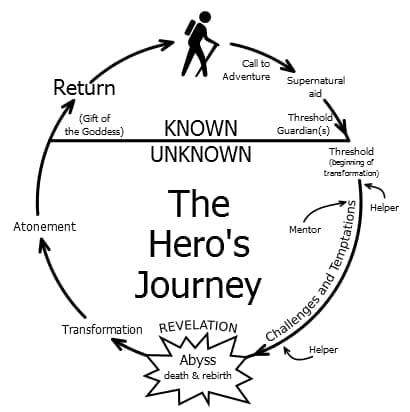

Historians, anthropologists, and mythologists have discussed the merits of mythology throughout the centuries. The most prevalent view today arguably stems from the concept of comparative mythology, developed by C. Scott Littleton. Littleton argues that mythological themes are connected through similar cultural constructs. Comparing these constructs helps us explore the cultures these myths come from, as well as the mythological tropes behind all of these mythologies to form a "protomythology," a sort of original myth that cultures would develop over time. Often comparative mythology goes through structural and psychological concepts, tracing language and themes from mythology into individual cultures. Through this, patterns emerge that feed into the protomythology theory, such as the Flood Myth, the Dying God, and of course, the Hero’s Journey through Joseph Campbell's Monomyth.

The basic structure of the Hero’s Journey is pretty much what drives the Legend of Zelda series. Everyone essentially knows about the plot already, at least in its barest form because the narrative rarely, if ever, changes by design. Link, as the chosen hero of the age through providence, answers his calling to go on a journey and defeat the forces of evil. He does this by collecting weapons and receiving help from allies. He solves puzzles and enters ancient dungeons to defeat minions of the dark forces and must overcome huge monsters to complete his quest.

It is the same structure in every Zelda game, not just because of the game design. From a narrative standpoint, it keeps the myth of Link alive. Since Link is a different character each time you meet him, his quest directly mirrors the tales of old mythology, which often mirrored each other through the comparative mythology theory. From a design aspect, much of the Zelda series also follows the same format as famous mythological stories, using mechanics to depict traits often seen in famous stories.

One example would be the collecting of items is usually a primary trait. Heracles traveled the world during his quest of the twelve labors and used different tools after defeating monsters for each labor. For instance, the second labor of Heracles was to kill the Hydra, a multi-headed beast. After slaying the monster, he then used the Hydra’s blood on his arrows, making them poisonous to the touch, and subsequently used his new tool to slay the Centaur Nessus later in his story. Heracles also used other weapons and items when in battle; his famous lion cloak was collected after he slayed the Nemean Lion and was said to be impervious to normal weapon attacks and the elements, while he acquired the Rattle of Hephaestus to confuse the Stymphalian Birds from Hera.

We see a lot of these aspects in Zelda as well. One of the draws of the game is collecting powerful items useful in completing dungeons and fighting off the game's dungeon bosses. The Fairy Bow, the Boomerang, the Hookshot—take your pick, because each item ever featured in the Legend of Zelda franchise had a function to it that aided the hero. They can be used against bosses to outsmart or overpower them in combat, or serve a utility purpose outside of battle, helping Link on his quest through various means. This parallels the use of items that many mythological heroes go through, adding to the mythological parallels of the Zelda series. It is of course easy to criticize the Zelda series for gimmicking each game, but that is missing the point of its design, as each game explores, often through gameplay, new ideas that not only follow Nintendo’s mandate to create a fun, memorable experience, but to continue the ongoing feel of a mythological structure.

Another common theme we see is the exploration of the world. Jason’s quest to acquire the Golden Fleece had him sail half of the known world to track down its location. Orpheus descends into the underworld to rescue the love of his life, Eurydice, from the clutches of Hades. While the destination is usually known by the hero, the journey to it is often long and filled with adventure and exploration, which is something we always see in a Zelda game. Link typically knows where he has to go; the journey is how to get there and what secrets can be found in the process. Other times, simple happenstance leads to a new avenue for Link; simple exploration in far-off worlds, islands or secret grottos gives the player a deceptively open-world feel that encourages players to explore the lands of Hyrule (or wherever Link may be) to uncover secrets that may help him in his quest.

While there are many parallels to mythological stories, one of the constant themes is that it’s a story told through tradition, so some elements always remain the same. In the case of Link, it is always a young boy or teenager named Link that goes on the journey of his predecessor. As described in The Wind Waker and Twilight Princess, it is often customary to name male children Link after the famous hero of legend, which is why the hero is also always the same name in the series, despite different timelines and worlds. Other similar factors include Link’s known left-handedness, the adoption of his style of dress, and the use of the Triforce and other symbols to showcase his only defined character trait, unflinching courage against impossible odds, and it is traits like this that keep the myth of Link alive game after game.

Carl Jung once said that myths are an expression of the culture's goals, ambitions, and dreams all rolled into one. If this is the case, then the character of Link’s endless courage can be viewed as a mirror of what gamers want to personify. Because The Legend of Zelda is an interactive myth that the player controls, and because Link, like many game protagonists, is of the silent variety, it is often noted that Link is not just a character in the game, but rather the projection of the person playing the game.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5myC-WBz5oM Modern mythology is often seen as derivative, because it lacks a cultural or religious tie to normal storytelling techniques. However, modern myths are still prevalent in popular culture, and some like Jung and others have argued that it is the next, logical step to showcase mythology in an age where mythical storytelling is antiquated. New phenomenon, like urban legends or creepypasta, have taken the place of myths, and modern media, from comic books, novels, movies and of course, video games. In that respect, The Legend of Zelda ranks among the top video game franchises to incorporate mythological storytelling into both their narrative and gameplay design.

Satoru Iwata stated in an interview about Zelda that “It’s a game where, once you become absorbed in the adventure, you don’t feel like you’re merely controlling the character, but that it’s really you pushing those blocks around. You really feel like you have solved those puzzles in the dungeons.” Nintendo is very keen on the fact that Link stands as a perfect representation of the immersive experience, a “link” as it were, connecting the players to the game world. This is perhaps why Link has no real personality per-se, since the players can project themselves onto the character rather easily.

It is also one of the best examples of an immersive character. Link, for 30 years, has been a pure representation of immersing the players into the experience. Changing the name and playing as Link during his adventures was likely the impetus of many nostalgic feelings for the legendary hero, because the legendary hero becomes the avatar of the player. So in a way, Link serves another function as a mythological character; he is the reflection of the player as the hero in the story.

Another function of myths, according to Joseph Campbell, is the pedagogical application of mythology. It basically is the use of myths to show people how to live under any circumstances. This works well with Link in the fact that he is the embodiment of courage, a virtue that is often associated as a positive in mythological storytelling. It is also a virtue that people strive to achieve in their real lives. People wish to be a hero at some point, and while true acts of heroism are often small and sometimes unreciprocated in a world that rarely cares, the courage and self-sacrifice we do in the real world is a reflection of the courageous acts heroes perform in mythology. So the connection that Link brings to the player is also one of self-fulfillment; a way to be the hero like no other in a long and arduous journey.

And that, to me, is Link’s strength as a character. Link is a symbolic representation of the hero in all of us, the hero we escape to when we play video games for enjoyment. We strive to be courageous in our own lives, in our own way, but collectively when playing as Link, we all share the same desires, the same goals of wish fulfillment. Our escapism is a fantasy; it is a desire for an ideal, but it is a reality if we apply such virtues to our real lives. That is the power of mythology, and, in a way, the power video games can have.

Yet for all the complex narrative structures, the long scenes of dialogue and an established character's own pathos explored within their respective titles, The Legend of Zelda has always been an exception to the rule because for me because of its mythological roots. Link becomes a representation of this ideal easily, which is why the love for the character, and the entire Zelda franchise, is near universal.

In the end Link is a memorable character because he represents the classic tropes of the mythological hero in its purest form, and through him we are able to project ourselves in such a story. Like any good myth, the common elements of each game only help to solidify the hero’s journey; it is a story you have played before, but it is always a fresh experience to go through. This, compounded with the symbolic Link has as an avatar for the players, makes him all the more mythic in his own right—leagues above many characters we see today.

I hope you guys enjoyed this article. Is one of my favorite characters, and it was a great pleasure to talk about him this month, in celebration of The Legend of Zelda's 30th anniversary. If you have any questions or comments, please leave them below or contact me on twitter @LinksOcarina. See you next time.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net