The modern era of consoles has brought with it a new type of gaming experience: Games as a Service, or GaaS for short. These titles, such as Destiny 2 and The Division, engage players with an online, ever-changing world in which they build a life. Featuring paid aspects called microtransactions, GaaS are a profitable avenue for publishers. However, that revenue may come at the cost of player satisfaction.

Service games are still in an early form. Game makers are still discovering the proper balance between pay-gated content and what to offer for “free." Each developer approach is an experiment. Some titles are successful while others close down mere months after release. No matter how one feels about GaaS, this new approach to game development represents a fundamental change in the way developers approach DLC.

How it has affected this online-focused generation of consoles is fascinating. But, with so many games—both single and multiplayer—incorporating service features, it’s important to pinpoint the start of this new phenomenon.

Establishing The Model

The last console generation brought about the rise of online play. During that time, we received some fantastic support for internet-connected games like Bungie’s Halo 3, Epic’s Gears of War 3, and Infinity Ward’s Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2. These periodic expansions were a downloadable form of disc-based content packs from the days of older RPGs. For a small fee, each one brought along new maps, weapons, and game types for players to enjoy.

With these packs, players could keep playing their favorite online games. As a result, developers would receive some extra funds for further projects. Yet, as the era of the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 came to a close, some games featured evolved versions of online content unlike anything seen on a console.

Microsoft’s adaptation of 1 vs.100 is one of the earliest examples of GaaS. Released for free in 2009, the game placed a singular player, “The One,” against 100 selected players, “The Mob”. Additional players were thrown into “The Crowd.”

The One would compete against The Mob for cash prizes or free Xbox Live Arcade games. Each week had a different theme of questions, such as Entertainment or Sports. Changing themes on top of monetary incentives ensured players would check in to see what’s new.

Microsoft was able to keep the game free thanks to advertiser revenue but canceled it after two seasons for reasons unknown. Even so, 1 vs.100 laid down a foundation that nearly every GaaS has followed since.

Microsoft’s primitive model was like an MMO. It implemented genre features such as the ever-changing world or incentives to keep players coming back, but in a unique, albeit limited fashion. But most importantly, the digital game show demonstrated that such a model could exist on consoles, and people would flock to it.

In their current form, many Games-as-a-Service titles are traditional single-player games with MMO features. 10 years ago, a game like Destiny would have had a single-player offline campaign and a separate online multiplayer mode. But the modern era has Bungie’s latest venture existing as an open, persistent world for both solo and team players to “live” within. While a continuous experience may seem like a gamer’s dream, the rise of these titles have seen their fair share of divisive decisions such as always-online or grind-focused gameplay mechanics. Most notably, these features have made their way into single-player games as well. This causes gamers with limited online connections to suffer, while also forcing solo players to deal with ever-expanding content in a game they may not want it from.

On paper, GaaS is a brilliant idea. Instead of releasing a one and done game and waiting years for a sequel, a service game has developers creating an experience and updating it every couple of weeks. These updates consist of new missions, areas, multiplayer modes, holiday events, and more. The idea is to engage players in a world in which they never want to stop spending time.

A majority of these extra content packs are free, though expansion packs for Destiny and The Division cost anywhere from $20 to $40. These prices led to frustration.

The Crux of GaaS

While some service-based titles like Dota 2, Fortnite, or League of Legends are free-to-play, others charge a one-time buy-in fee. Games like Overwatch, Star Citizen, and Rainbow Six: Siege come to mind. At the crux of service-based games are microtransactions: small fees for in-game items like skins, exp boosters, and other cosmetic changes. Developers of both free and paid services incorporate microtransactions to keep updates coming without charge. Usually, these changes are optional, and those who bought the game can enjoy all future updates without spending extra. While they can be annoying, microtransactions are a small thing to deal with in exchange for an ever-changing game. If handled correctly, that is.Late last year, a little game called Star Wars Battlefront II released. As an online-focused reinvention of the popular PS2 franchise, it’s not surprising that DICE’s sequel preyed on that nostalgia with microtransactions. What was surprising is how intrusive and game-ruining these charges were.

To quote fellow TechRaptor writer Anson Chan, Battlefront II’s microtransactions “aren’t perks that provide niche benefits or severe tradeoffs in exchange for minor buffs either, these are perks that anyone would equip without a second thought because they give you an indisputable advantage over someone who doesn’t have these perks.”

Even worse is that players could not choose which benefits they were paying for. Instead, they were paying for the opportunity to receive a randomly generated reward from a feature called a lootbox. These randomized gifts are a common trope in GaaS titles, with Overwatch having popularized them. Players are paying for the chance at a game-boosting item. The rarer the item, the lower the probability of receiving it. Again, the exchange for microtransactions is free DLC. But when the charges are this invasive is that trade-off a win for the players?

Battlefront II’s lootboxes caused such a stir that non-gaming outlets such as CNN had reported on them. That’s not to mention that their randomized nature generated discussion on whether or not lootboxes are gambling. Eventually, DICE and EA reworked these charges, but the damage was done.

Despite that tragedy, worse is when microtransactions began creeping into solo games such as Dead Space 3. This trilogy-capping title saw EA and developer Visceral Games introducing micro-transactions into a campaign-only experience. Players could pay money for better weapons instead of having to craft them in-game. Sure, you could get all of these items in-game, but the option was there for players willing to spend on top of their sixty-dollar purchase. Players protested this decision, claiming it ruined the immersion and unfairly enticed players into paying extra.

John Calhoun, a Producer at Visceral, defended the decision, arguing that "There's a lot of players out there, especially players coming from mobile games, who are accustomed to microtransactions.” He continues, “they're like, 'I need this now, I want this now.' They need instant gratification. So, we included that option in order to attract those players, so that if they're 5000 Tungsten short of this upgrade, they can have it."

Calhoun then claimed that there was no “pay-to-win” aspect, so the option shouldn’t be an issue for anyone. However, the inclusion of a pay system alters a game regardless of its portrayal. How do we know the crafting system isn’t unfairly pushing players towards paying? Did the developers balance out the difficulty with these options in mind? A store like this leads to a dirty-feeling experience. That said, Dead Space 3 is a minor blight when compared to more recent single-player microtransaction systems.

Monolith Games’ Middle-Earth: Shadow of War was the sequel to GOTY breakout Shadow of Mordor. The title enabled players to build their own army of orcs, with the endgame consisting of an all-out battle. But, getting to that end fight required a ton of grinding with only one alternative route: lootboxes. As you can imagine, players were not happy about that.

Shadow of War did have its share of free content updates. Monolith added a post-game mode, additional weapons, and much more. But, it represents how GaaS features have seeped into every aspect of the industry. Despite players paying full-price for a fleshed out single-player experience, they were forced into hours of monotonous grinding with coughing up cash as the only way out. Like with Battlefront, these pay-to-win aspects were removed, but after months of player complaints.

Contrary to popular belief, not all lootboxes are awful. Rocket League introduced this type of microtransaction a little after its release. Known as crates, these items can drop after a match. But players can only open containers by purchasing keys. The lootboxed items are cosmetic, including new cars, skins, wheels, player banners, and more. In fact, item implementation created a trade economy within the game and encouraged community interactions.

Aside from some exclusive DLC cars, everything else in the game is free. We’ve gotten years of new stages and game modes because of it. For players who still can’t stand them, developer Psyonix even provides an option to hide crates. This is one of the best approaches to microtransactions we’ve seen this generation, and Rocket League has thrived because of it.

Assassin’s Creed Odyssey hands out free lootboxes as well, but you don’t have to pay to open them. Instead, these randomized crates offer a low chance at premium items that aren’t even the best in the game. Rather, this gear is aesthetically more experimental than the traditional pieces. Special items like XP-boosters and item-revealing maps must be purchased with real money, however. Yet, these item maps pay for themselves in that players will find collectibles worth more than the price of the map. It’s a player-friendly approach that still benefits developers.

A Unique Approach

Final Fantasy XV took a different approach to the service game. As a colossal single-player RPG with no multiplayer mode—at launch, that is—fans received the epic single-player journey they expect out of the franchise. But despite its decade-long development time, the latest Final Fantasy suffered from irrefutable plot holes and shoddy character development.

Shortly after release, developer Square Enix announced these shortcomings would be addressed via a combination of paid and free character-focused DLC episodes and updates. That and Square revealed a years-long roadmap of extra content for XV with new events coming at a monthly rate. While more content is generally a good thing, the plot hole debacle proposes a broader discussion: are developers releasing unfinished games to charge for extra content later?

In most cases, that claim is an overreaction. Game development is strenuous, and content is always cut. Developers would be remiss to leave that material in the trash bin instead of reworking it into a good expansion. However, DLC such as Mass Effect 3’s Javik served to be early fuel for that conspiracy.

As the first living member of a race so core to the Mass Effect experience, Javik the Prothean should come with the base game. Yet, EA and Bioware dared to charge $10 for Javik as launch day DLC. If EA charged players for a reveal that players have been waiting for since the first Mass Effect, should we have been that surprised at the Battlefront II disaster?

In a similar vein, Microsoft’s Sea of Thieves released this year to less than stellar reception. As a $60 title, the game portrayed a beautiful but ultimately shallow world to explore. A lack of meaningful progression and weak gameplay topped everything off. Developer Rare failed to produce engaging experiences. Instead, players were encouraged to create their own. Yet, with so little to do, it’s a wonder as to why Rare released the game in this state. We know that microtransactions will come at a later date, and all DLC will be free.

A content-lacking, “early access” approach to development has run rampant this generation. As service games in their own right, early access games tend to be half-finished experiences that players can invest in during development. In return for their money, the community often has a say in which direction the game should go. Games like the recent Dead Cells have seen great success in this approach.

In fact, team members from the now-defunct Runic Games, developers of Torchlight and Hob, are putting together a new studio, Monster Squad Games, to focus on GaaS. In an interview with PC Gamer, studio lead Marsh Lefler revealed that despite the success of the Torchlight franchise, once it was finished, they were “done and onto the next project.” Lefler continues:

“Now, it seems players want games that constantly grow and evolve. Early on, we … realized whatever we were going to make needed to be something we all could work on for years to come with our community, and we all needed to love it. It's really motivating to make something and then put it in front of players right away. You find out what works, what doesn't work, and what's missing really fast, and if you put things out right after making them then the community can be a real part of the conversation about what the game is going to be.”

Ironically, but no less tragic, Runic was shut down so publisher Perfect World could focus on service-based games. While some former members landed on their feet, the fact that Runic was closed in the first place shows just how much money Games as a Service bring in. According to a report, GaaS had “tripled” the value of the games industry in 2016. An excerpt from VG/27 reads that “a quarter of all digital revenue from PC games with an upfront cost came from additional content.” These profits mimic the mobile market and web games like FarmVille, which featured microtransactions long before console games did.

At their best, microtransactions are a rewarded donation to one’s favorite developer. At their worst, small payments are brash attempts at forcing more money out of a player. There’s a lot of room between those two extremes.

GaaS And The Rebirth of A Title

A service approach can also bring new life into a game. Rainbow Six: Siege, Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn, and Warframe are all examples of flopped titles that rebuilt their way into popularity. Each one features a thriving community, with Warframe being the go-to model for a successful free-to-play service game. Team Fortress 2 went free-to-play with microtransactions years after release, allowing a new generation to experience the magic.One single-player indie title, Renowned Explorers, was led to success thanks to a GaaS model. As a strategy game that released to little fanfare, developer Abbey Games decided to keep with it and create some expansions. “Renowned Explorers wasn't designed as a GaaS title, but it's [sic] content-focus made it suitable for it,” revealed a spokesperson from Abbey Games. He continues, “we could create new expeditions, characters and gameplay features that all improved the base game. Our philosophy in how to expand the game is very much inspired by how Firaxis updates Civilization. They did small content packs, but were ultimately most happy with the large expansions they did.”

Because of this dedication, Renowned Explorers gained a cult following and has been a financial success for the studio. In fact, that funding is going into a new service game right now.

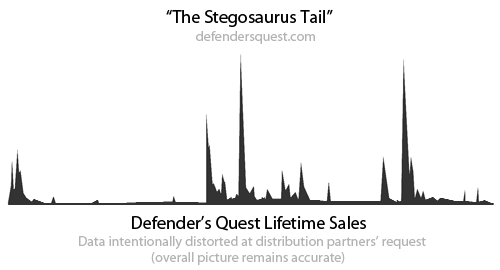

Abbey Games’ triumph isn’t unheard of either. The profits from Renowned Explorers are representative of something called “The Stegosaurus Tail,” or at least a modified version of it. The Stegosaurus Tail is already an altered version of something called “The Long Tail”. This phenomenon comes from Chris Anderson’s book, “The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More”. This is a sales model that represents hyping the hell out of your game until release and making a ton off initial sales before they taper off. Once released, you abandon a product and move on to the next one. But that model can’t apply to those with no marketing budget. Sometimes, you have to put a ton of work and polish into one title because that’s all you can afford.

As an alternative, Lars Doucet, developer of the Defender’s Quest franchise, takes The Stegosaurus Tail approach. Here, the initial sales are still significant, but instead, there’s a focus on post-release content. When releasing the first Defender’s Quest, Doucet reveals that he and his team worked on “improving the game to catch Steam's attention." New game+, an upgraded art style, and other updates led to promotion of the game each time. Doucet and team partnered with GOG, Steam Workshop, and more. As a result of all this promotion, they saw spikes in sales which resembled a Stegosaurus Tail. After all this promotion, the team now has funding for a second game alongside a dedicated fanbase looking forward to the sequel.

That said, committing to one game only works if people play it. An over saturation of ever-expanding games means that there isn’t room for everyone to win. Battleborn and Gigantic (the latter also owned by Perfect World) two stylistic titles ripe with service elements, had shut down less than two years after release due to a lack of funds. Even worse is Radical Heights, a battle-royale game from Cliff Bleszinski of Gears of War fame. Only one month after release, Bleszinski’s studio Boss Key Games revealed it would be closing its doors. Even as a free title, Radical Heights struggled to gather a player base. A lack of players means fewer microtransactions. That combined with no entry fee means no way to pay employees, leading to eventual studio shutdown.

The issue, Cliff revealed, was that his game was “too little too late.” Radical Heights was an attempt to jump on the battle-royale trend popularized by PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds and Fortnite. Unfortunately, the studio suffered a similar fate with their first game, Lawbreakers, in 2017. Boss Key’s first attempt was a team-based first-person shooter that launched into a market where Overwatch had already captivated the target audience. Lawbreakers was well-made, fun to play, and even released at a discounted forty bucks. However, it chased a trend that was already oversaturated. Despite its widespread marketing campaign, the game had hardly established a player base. While well-intentioned, both of Boss Key’s titles are prime examples of how a studio can fail even with star power and marketing money behind it. Neither release was particularly unique, but no one could have predicted such significant failure.

While GaaS can go either way financially, proper ones bring great value to players. Becoming immersed in one title saves gamers money, and it provides a space for communities to grow. It’s much easier to convince non-gaming friends to try out one title—look at Fortnite! Gamers without a ton of time can focus on one service game and get their fix too.

Experimenting Within The Genre

On the experimental side, IO Interactive took the GaaS model to a new level with their Hitman reboot. While initially shunned, the team took an episodic approach to everyone’s favorite assassin. Each episode introduced a new level with dozens of different paths and solutions. The timeframe between updates enabled players to experiment and learn the levels rather than rush through the plot line. Then, IO continued support with time-limited “Elusive Targets” encouraging players to jump on and delve into another round. Released last month, Hitman 2 will not be episodic, but it will continue the elusive target trend.

It’s essential for developers to experiment with the GaaS model to keep players engaged. In Hitman’s case, IO revitalized a franchise and brought it back into the forefront of gaming. Monster Hunter: World utilized the service model to deliver a niche, often handheld only franchise to the mainstream. Monthly updates brought in new monsters and timed missions, creating a living world for players to come back to.

That said, not all franchises benefit from a service model. Sometimes gamers want a consolidated, story-based experience to engage with. If an IP doesn’t cater to a GaaS cycle, its consistent world could be its own death sentence.

For example, Bioware’s Knights of the Old Republic games were lauded for their storytelling and worldbuilding. Then, for some reason, the team decided an MMO was an excellent idea for a sequel. The hype was real as Star Wars: The Old Republic broke EA’s previous number of pre-order sales. Yet, upon release, the MMO elements were cookie-cutter and serviceable at best. Fans praised the instanced story elements that can be played solo or with a small group of friends. Unfortunately for the MMO, these were all features that could exist in a fleshed out single-player RPG experience. As players completed the story, sub counts fell and the buy-to-play, monthly subscription title went free to play less than a year after release.

It’s not just Bioware, however. Nearly every game incorporates GaaS elements in some way. Forza Horizon 4 is a living world with regular events and updates. If GTA V is anything to go by, we can expect Red Dead Redemption 2’s online mode to have weekly content updates.

Fortnite’s Battle Royale mode has long been experimenting with the GaaS approach in its narrative. Earlier this year, a random comet appeared in the sky during Battle Royale matches. The game played exactly the same, but this small change generated interest and discussion all over the internet. That comet ended up crashing and introducing fun new gameplay aspects like low gravity and even brought in new areas.

Instead of leaving the multiplayer as is, Epic Games have been upgrading the Fortnite Battle Royale experience to keep players engaged and talking about it. Players would argue for weeks over where the comet would hit and how it would change the game. Those who have taken a lull were more likely to jump back in and check things out. Then, those players having the most fun will buy microtransactions to deck out their characters. Everybody wins.

Regardless of your feelings towards this surprise hit, Epic’s balanced take on the GaaS experience is admirable. Not only do they generate conversation around their title, but they bring in narrative and flesh out their game world. It’s a best of both worlds that’s only possible with the service-based approach.

Fortnite’s take on GaaS echoes the Vice President of Psyonix, Publishing, Jeremy Dunham, in his advice to game developers looking at service-based:

“Make sure it makes sense for your design. Make sure that you have plenty of things for people who have already invested in your game to do, regardless if they ever pay you another cent or not. Don't put levels or features that depend on high player counts behind any kind of unnecessary paywalls. Players are not dumb, nor do they have a lot of time. You're competing with other games in and out of your genre, along with streaming services, real-world events, television, and all the school and work schedules that come along with being alive. You need to present players with the best thing about your game right upfront -- you have to show them that you believe in your game so that, in turn, your players will believe in you. If you don't approach your audience and design with that kind of mentality, then you're probably already faced with more challenges than you wanted.”People have to enjoy your game before you can update it. Dunham claims that when making Rocket League, GaaS wasn’t their “main focus.” Instead, Psyonix prioritized “making the game rewarding and fun to play.” As time went on, players requested more and more content. That engagement served as a cushion for the small team and enabled them to focus on monetizing their content. Minecraft and Terraria benefitted from this model as well, as it allows developers to work with their fan base when creating updates.

There’s no question that Games-as-a-Service is here to stay. The profit margins are too high for game makers to ignore. That said, while GaaS has shaped most of this generation, we’ve also yet to see all the ways it can be explored. Rainbow Six: Siege, Hitman, and Fortnite are all shining examples of how this model can work. But, as profitable as service games can be, developers must take heed of the industry. It's vital to examine whether their title can stand out. One-and-done experiences are still valuable and still make up most of the best games seen this generation. Not every title can attempt to take all your time and money. As we roll into the next generation, we must understand that when every game strives to be your one game, no game can be.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net