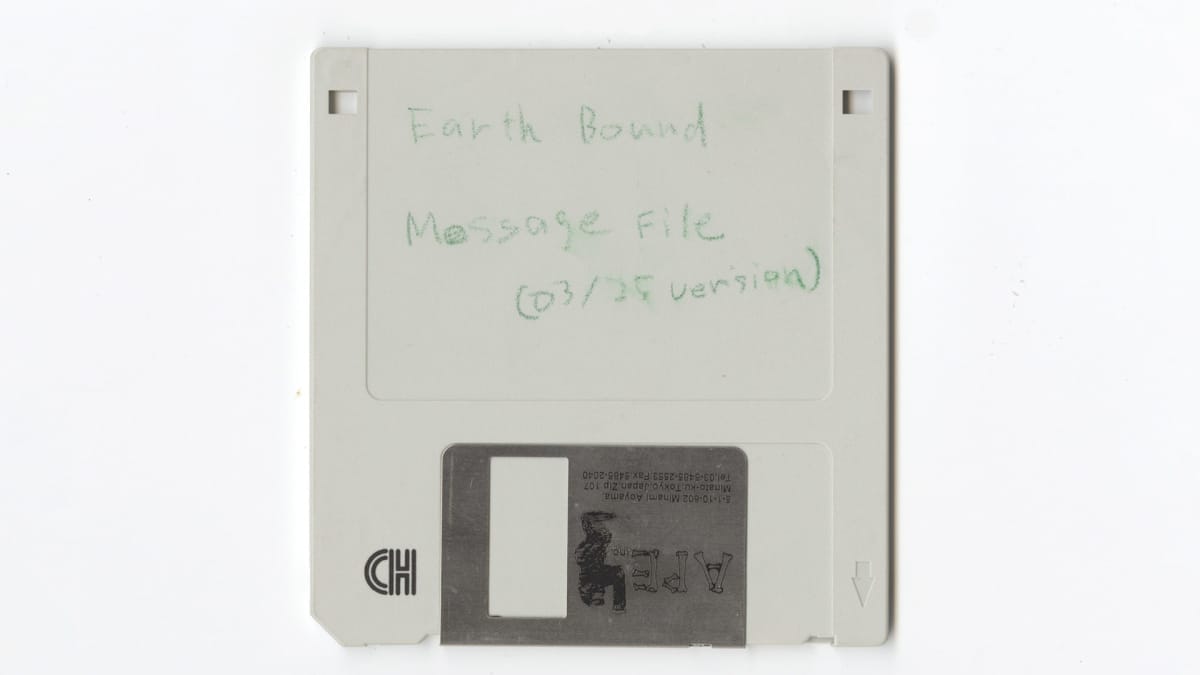

Back in June, the Video Game History Foundation published a piece on the critical darling Earthbound. The news about Earthbound was not a long-lost demo or copy... but scripting code that was long deleted by translator Marcus Lindholm back in the 1990s. Frank Cifaldi, the founder of the Video Game History Foundation, was able to perform some digital forensics to recover this long-lost relic. With it, a whole video and article were produced to showcase differences in the script from development to completion for curious gamers to read.

Some may question why recovering a small amount of scripting code is so important; after all, Earthbound is a popular game that is still remembered fondly by players. It leads to a major issue regarding gaming preservation: simply how misunderstood the practice actually is.

The One-Track Mind of Game Preservation

Some gamers do not understand game preservation. I know, it’s a bit of a harsh claim, but it really does feel like wheels spinning in place whenever a discourse about preservation comes up. It often becomes a circular argument that focuses on one single point: The games should be freely available, all the time, to the public.

It is an infuriating charge, especially in how misguided it becomes. One thing I constantly see, in reference to the conservative nature of Nintendo, is how they are horrific at preserving their own history. This especially comes up when titles like Earthbound rarely see a re-release. Many Nintendo games suffer this fate, being a product of their time and console, with re-releases few and far between.

You would think though, the massive leaks that occurred over the past few years would prove that claim wrong. The Giga Leak pretty much dumped troves of history and development of Nintendo products, games, systems, and more into the general public. It was an impressive find that was part heist and part archeology, and it has led to newer discoveries long after the Leak has subsided, such as publicly seeing the long-lost WorkBoy actually function thanks to the efforts of historian Liam Robertson.

Gaming preservation is more than just having unfettered access to a final product.

Here is the thing: Nintendo is not bad at preserving their history. In fact, they are damn good at it as those leaks showed. Unlike other companies, which have been public about lost or corrupted ROMs of their own titles, Nintendo seems to have a massive catalog of preserved code and products locked deep into their vaults. This is a net positive in the end; a trove of materials kept safe for nearly 40 years is impressive. The issue people take umbrage with is the lack of seeing inside that vault and getting to play.

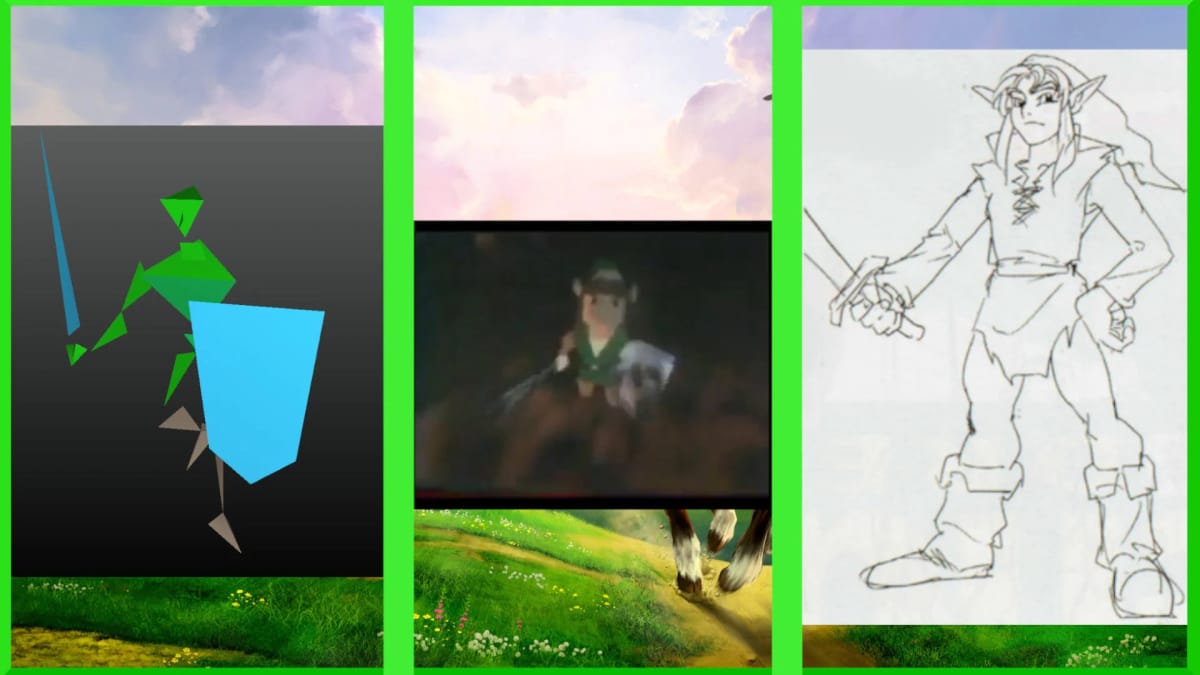

Gaming preservation is more than just having unfettered access to a final product. Keep in mind what good preservation is: It is part digital archeology, part archival work, part storyteller, and lastly part experience of play. Something as simple as archiving source codes is the core of any form of digital preservation, but it goes beyond just that. A lot of this is seen in anyone who has an inkling of interest in true preservation, the whole story archived from development to release. My own (admittingly limited) example of this, chronicling the entire development process of The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, was a herculean effort of going through dozens of sources, translated materials, video and photo archives, and yes, the Nintendo leaks, to just make a timeline of the development.

Experts like Cifaldi, who have more technical knowledge than I will ever possess, focus on multiple facets of preservation. While being able to play a game is important, so is interviewing coders and developers, as well as documenting posters, magazine adverts, and release materials. You can search for design documents and source code, recover hardware specs and prototypes, and employ every trick in the book to recover data lost to time. The discovery of simple things like script changes in a cult classic such as Earthbound is emblematic of the part of preservation we don’t often speak about.

Most of this material is donated to them by either the publishers, developers, or through emulation. Game preservation is not about just preserving the games. It’s about preserving the whole history, the whole cycle of development right down to the broken codes and diluted sprites. Even amateur teams do this well, such as Forest of Illusion, which has continuously showcased the development findings of games for the past few years.

Selective Game Preservation

Forest of Illusion, a preservation group focused on Nintendo, is valuable for their efforts because they are uncaring of what is preserved or discovered. Take, for example, their Prototype Shovelware Collection, which is a small trove of games for the Nintendo DS that were in their prototype phase. These popular titles include the classics General Knowledge for Dummies, Animal Color Cross, and two copies of Easy Piano!

The thing is, good preservation doesn’t care how famous your game is. It is very unlikely anyone is clamoring to play Easy Piano when compared to Earthbound, but both should be equally saved as much as possible. Gamers often focus heavily on what is popular or interesting to them, which is why some of the more detailed preservations efforts are the ones focusing on popular franchises.

For example, did you know that Midway Games was working on an MLB game that was in the same vein as NBA Jam? Titled Power-Up Baseball, it was an in-development prototype discovered on a disk that thankfully has not been degraded yet by programmer Chris Oberth. If this sounds cool, that’s great, but for most gamers out there, seeing footage and assets of a canceled MLB game is not exactly in the same league as a prototype Zelda ROM.

More games are often than not in the vein of Power-Up Baseball or Easy Piano, games that fall into obscurity because of their limited impact in the grand scheme of the industry. There is nothing wrong with that either; not every game needs to be a blockbuster. Every game, however, deserves to be preserved and remembered, no matter how minor they are to the story of the industry, and for a majority of games, they are running out of time for that preservation.

The Piracy Problem

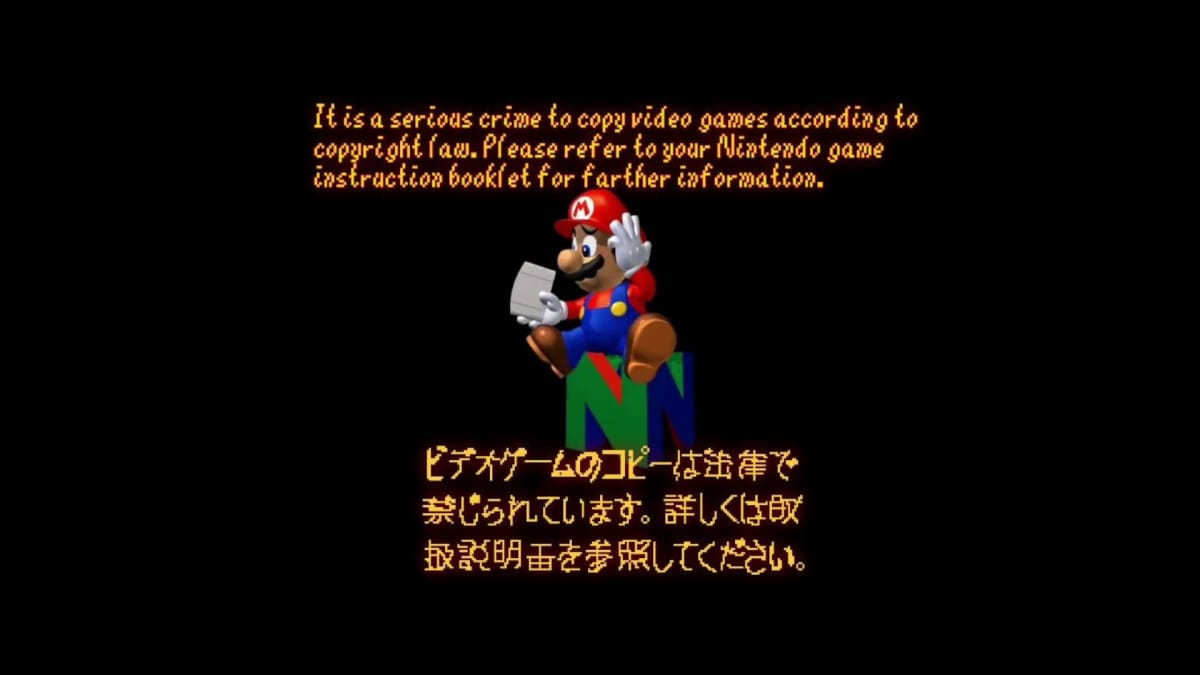

Preservation, as many know, is in a gray area of legality. It is well known that emulation, which is often used to play preserved ROMs, has a mixed legal reception in regards to how publishers and the law often protect their intellectual property. Technically emulation itself is legal; the problems arise through piracy, where illegally obtaining or ripping ROMs to play on an emulator places it in a very precarious position.

On the one hand, it is somewhat romantic to be a part of a grassroots preservation movement by bravely defying the law to save something you love dearly. On the other hand, the problem with piracy is one of abuse and misguided attempts at activism to mask true motivations. Make no mistake, the true benefits of piracy are few and far between, and even in those bright spots where they are beneficial, we should be able to call out piracy for what it truly is: selfish behavior.

See, creating ROMs is not always a foolproof way to preserve a video game in full. Even those deep into the preservationist culture, like Cifaldi, mentioned multiple times that he "can’t guarantee that the person who copied a disc didn’t accidentally mess up something that changes the game.”

This doesn’t mean ROMs should not be used, but it does mean that careful care and an understanding of how to use emulation should be employed. A few lines of code and data are all the difference between a 100% authentically released product and one that is tainted and incomplete. The intentions of releasing an emulated copy of a game online, while noble, can be disastrous for archivists looking to salvage the authentic game.

Accuracy also takes resources and power. Ars Technica wrote back in 2011 about this process, going into detail on how to create as authentic of an experience for SNES games as you can, right down to the right timing that consoles would imitate with their processing power. Why does this ultimately matter? Those looking for pure emulation, and true preservation, would care about a small difference in the timing of the game.

“As an example, compare the spinning triforce animation from the opening to Legend of Zelda on the ZSNES and bsnes emulators. On the former, the triforces will complete their rotations far too soon as a result of the CPU running well over 40 percent faster than a real SNES. These are little details, but if you have an eye for accuracy, they can be maddening.” - Ben Kuchera, Ars Technica

The eye for details like this is the difference between selfish and selfless emulation, putting the work in for the true experience. It is little things that get lost in these preservation efforts, like a shadow or two in an emulated copy of the game, because the processing to render it is too resource-intensive. Or how about a game like StarFox, which was notoriously slow and choppy on the SNES, suddenly running smoothly on an emulator with slightly upscaled graphics.

It’s easy to upgrade and make a game run better for you. It’s nobler to let it stay imperfect for everyone to enjoy it as it was.

Game Preservation - What Can We Really Do

So what can we do? The answer is sadly not so simple, though there are three low-cost ways to maybe contribute without breaking the law - or the bank.

First, keep the memories of obscure games alive. Everyone knows who Mario and Zelda are, but extolling the praises of your favorite Mario knock-offs, both good and bad, is at least a sure-fire way to mark their continued existence. One thing that is seen online serves an archivist-like purpose is footage (from imperfect emulation sometimes) of games in full, showing off menus, features, whole gameplay modes, and so on. Longplays, in particular, are a good source for this, sometimes providing a look at a game that has long since been disregarded or forgotten.

The second is to put pressure on publishers to preserve their content better, regardless of cost. This does not mean the content should be available to you freely, but rather that the content, from development to subsequent releases, be secured and preserved. That as a starting point could open up the conversation for companies to be more willing to showcase aspects of a game’s development with the fear of losing trade secrets or dealing with copyright claims.

Lastly, we need to support full preservation efforts. Groups like Forest of Illusion or the Video Game History Foundation should be shared and celebrated for their works, and those looking to truly help with preserving gaming history should provide encouragement for the cause, be it donations or simply spreading the news to the greater gaming audience. This is not just the efforts on big games, either, but for the little victories they talk about in their archiving efforts, like those extra lines of code for Earthbound.

After all, once we care about a few lines of code, that is when we begin taking preservation seriously.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net