Another one of the people I didn't get to meet at Playcrafting's Fall Expo was Robert Brown. Robert was showing off a board game which was a bit of a rarity at Playcrafting—there were only a handful of board games compared to video games.

Robert's game is called QuestFour and involves an understanding of spatial reasoning. That's about all I knew about it going in to this interview. I later found out that it delivers everything it claims to, and it is a game that is to my mind a worthwhile investment for an educator, a parent, or anyone who enjoys games that give you a little bit of mental exercise. Here's my chat with Robert Brown where he talks about how he came up with the idea for the game and his motivations behind its creation.

TechRaptor: First I want to extend my apologies for just not being able to talk with you in person at Playcrafting. I passed by your table a whole bunch of times and I got a pretty good look at your game but you were always occupied with somebody and I didn't really get the opportunity to sit down with you one on one. I'm sorry I wasn't able to make that happen.

Robert Brown: I was thankful that a lot of people wanted to play my game.

TR: If anything, that speaks to people's curiosity. The fact that ... I passed by probably about every ten minutes over the three and a half hours Playcrafting was running and there was always somebody [at your table]. I didn't catch you in a moment where you were by yourself because if I had I would have rushed up and spoken to you.

TR: If anything, that speaks to people's curiosity. The fact that ... I passed by probably about every ten minutes over the three and a half hours Playcrafting was running and there was always somebody [at your table]. I didn't catch you in a moment where you were by yourself because if I had I would have rushed up and spoken to you.

RB: I'm glad that we were able to connect afterwards.

TR: The first thing I noticed [about your game QuestFour], it seemed—just from the glance that I got it—I'm guessing that you had your prototype model with you there? Is that correct?

RB: Yes.

TR: So does that mean that you're currently in the prototype phase for the game or are you already in production and just the prototype what was you had with you?

RB: Still in the prototype phase. I was originally hoping to launch on Kickstarter in the fall [of 2015] but I was still getting some issues with the instructions. It just wasn't playing out for people with instructions the way I'd like. I decided to tear them up and start from scratch. When I'm with people and have a conversation with them it's much easier to get the ideas across because, you know, people have a tendency of equating any information that they're given to something else that they already know. So they'll take a look at the game and they'll say, "Oh, that's kinda of like Connect Four" or they'll mention some other [games with similar mechanics]. And it's not until they actually get to play the game that they go, "Oh. [It seems simple at first], this is really cool... oh my god, this is hard."

TR: There's this lovely site called BoardGameGeek.com and it has your instructions on there. Did you put that up there?

RB: Yeah.

TR: Oh, so that was you that wrote all that out. Are those the instructions that you're scrapping and re-doing or is that the new version that you're still working on?

RB: If it's the instructions I'm thinking of [that's] actually the full instruction set, I have not loaded the newest instruction set. The newest instruction set is gonna be more graphics than it is verbiage. That's where my problem was. The game - because it's three dimensional and most people don't think in 3D - they needed a visual companion to understand what I was explaining. Even when I explain to some people they still get lost and I have to go back to explain it to them again. Trying to work through that and working with my graphic artist to get that done is where I'm at right now. So I decided to postpone the launch.

TR: Have you ever seen Star Trek: The Next Generation?

RB: Yeah.

TR: You remember they had the 3D chess in that show?

RB: Yep, yep.

TR: Now that's an actual version of chess that they produced and you can buy. It's ungodly expensive—it's like $150 for the board. And it has actual rules. I know how to play chess. I read the rules and I still can't wrap my head around it and I think you're encountering the same kind of barrier where even though the instructions [are] very clear and very explicit but some things are just difficult for people to understand them if they're not shown them. And you say you're having the same problem. I understand that—I've done work in IT and I've had to do technical writing. Something like, you know, "this is how the networking is all set up" - I can explain it to somebody in [under] 5 minutes but it took me hours to write out 35 pages to detail stuff. The general idea is, "What if I get hit by a bus? Nobody knows how this stuff works. So I have to explain everything [in extreme detail], very clearly, and make sure no details are left out. I imagine writing the rules for a board game is the same way and it's probably exacerbated by working in three dimensions and something that people really aren't used to.

RB: Yep. I'm actually in IT as well, that's my day job. Doing requirements and technical design is something that I'm familiar with. But to get to the non-technical person who doesn't think necessarily in that very specific, concise manner...

TR: It's a mindset.

RB: It's a mindset and most people need a visual component to reinforce the verbiage that they're reading because it just helps connect it.

TR: What was the motivation for you creating this game?

RB: I'm a father. I have a genius twelve year old. Back when he was nine, ten... he's part of Mensa, and Mensa in New Jersey & Pennsylvania does not have a kids support group.

TR: Oh, so when you say "A genius twelve year old" you're not being a doting parent. You mean [your son] is actually measured at the genius level.

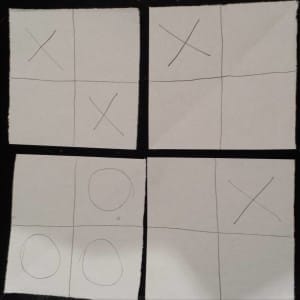

RB: Yeah, he's actually in Mensa. And because there was no kids group. He likes interaction with people his own age. Because I couldn't find other kids of his own ability I thought, "Okay, well I need to come up with some way to keep engaging his mind." I played verbal D&D with him so he has to track what the characters are doing verbally in car rides which helps build his vocabulary and his visualization skills. Just off the top of my head I was like, "Let's do something a little bit different that helps work on his spatial reasoning." Tic-tac-toe came to mind [and I thought], "What if I do it on these four boards with four squares each that way the boards rotate?" So we started out on paper. I would just take a sheet of notebook paper and tear it into four squares and draw grids on all of them. We'd play tic-tac-toe where you have to get four Xs or four Os in a row with the boards rotating. We played that for a while but it became very easy for him. And so I was like, "How can I amp it up? How can I make this three dimensional?" It took me about two months to come up with the tube design. I had thought about creating [QuestFour] as a mobile app but decided not to because digital is pervasive in our society and kids could just continue to manipulate the visual until they found the pattern that they were looking for. That's not what I wanted for [my son]. I wanted him to mentally visualize what had to happen - building his spatial reasoning. After I came up with the tube design I created the 3-D files, sent them off to one of the online printing companies. They printed up one set for me. I got those back and I made some molds and molded an entire set. That's the set that you saw at Playcrafting.

TR: It looked a little bit rough. I assumed, naturally, it was probably something homemade because the edges seemed a bit rough so I figured [it was made of] PVC pipe or something like that. I looked at [the QuestFour prototype] and [think], "If I wanted to make that, that's a trip to the hardware store and some painting."

RB: The first version was actually PVC pipe. It seemed to go well but the center piece because it was half-inch PVC was a little bit too wobbly for two inches high. I realized that I needed to make a different dimension. That's when I sent the files off to Shapeways (an online 3-D printing service) and [they] printed them up. I went to this company in Pennsylvania called Smooth-On. They sell a variety of molding materials. Some of it for industry, some of it for theatre. I bought one of their molding kits and made a mold of that first set from Shapeways. Yeah, it's handmade, it's rough, but there's a nice weight, there's a nice texture, and it gives you that 3D representation. Now you have to work in the X, Y, and Z axis with tile rotations and that's where [my son] really had to start thinking. He came up with his own strategies. People that played the game - it's not a matter of age. I've had eight-year-olds beat kids in college. It's your spatial reasoning. I started doing some research and found that there's actually a spatial learning lab at Temple [University]. I spoke to Dr. Nora S. Newcombe who runs that lab and she has done some research that proves by playing games that help develop your spatial reasoning you can actually improve it which is kinda cool.

Mr. Brown provided me this link (PDF) to Dr. Newcombe's article "Picture This - Increasing Math and Science Learning by Improving Spatial Thinking".

TR: You brought up the idea of strategy. Because you're making a game from scratch you wholly decide what the elements are. You went with a board that's 4x4x4 at its maximum. That's the space you work within. You don't stack a tower any more than four high, correct?

RB: Correct.

TR: And you were saying earlier that you tried 3x3x3 with your son but it was too easy and I'm guessing 5x5x5 is too hard so 4 cubed is the ideal middle ground where it balances challenge without being too hard and the game running too long.

RB: Right.

TR: Did you try playing 5x5x5 or did you just do 4x4x4 and [thought], "This is good enough, we don't need to go any bigger."

RB: There is a game out there that has four boards where you have to get five marbles in a row. I never even knew about that game until I had done the prototype. I was someplace playtesting and [someone] said, "Oh, this looks like [this game]." I said, "I've never heard of it, what is it?" I looked it up on my phone and I was like, "Oh, yeah, okay. They have four boards that rotate and players have to get five marbles in a row but it's not 3D so I liked the completeness of what we had designed and decided I didn't want to go into five.

TR: Pentago. I [knew] saw something similar [to QuestFour before]. Because I remember a game where you picked up the board pieces and rotated them. So you created QuestFour without even knowing that similar board rotation mechanic [existed in other games]?

RB: Exactly.

TR: Pentago still only works within two dimensions so [QuestFour adds] another layer on top of that.

RB: Right.

TR: Are you familiar with the concept of a solved game?

RB: No.

TR: Okay. When it comes certain games there's something in game design called a "solved game." What a solved game is—I'm just gonna read straight from Wikipedia here—"a game whose outcome - win, lose, or draw - can be correctly predicted from any position assuming both players play perfectly." So that means essentially every possible move from every possible position is figured out and if you have that knowledge—say if you were a computer. A computer could make perfect moves and essentially win and the only way the computer doesn't win is if the other player [doesn't make] a wrong move. What's the fewest number of moves that you can recall offhand that someone was able to win a game of QuestFour?

RB: I have typically been able to win with a novice player in four moves. I have met some novice players whose spatial reasoning blew me away and I've had a stalemate with them.

TR: So a stalemate's actually possible in the game where you can't win essentially.

RB: Where you actually have to place all of your pieces on the board and neither one of you end up winning. I've also had a few ties - where when you rotate for that last move both players have a winning position.

TR: Do you have contingencies for those situations in the rules? If a stalemate happens or a draw happens [you decide the victor] some other way or is that something you're still working on?

RB: No, you know, for a stalemate you just have to replay. And for a draw... I didn't envision a draw. I look at this... there are some people that are really hardcore strategy folks. My brother was a rated chess player. And I just didn't want to memorize so he gave me a book when I was 8 or 9 and said, "Here. 1,000 opening chess moves." And I'm like, "I don't want to memorize this." [laughs] Board games are about just spending time people that you enjoy spending time with and doing something that's fun. Every Wednesday night there's a local board game group that meets and it's mostly adults but it's [my son and another child] and they go as well and we go play a bunch of different games like Illuminati or Puerto Rico. A variety of things that keep engaging him.

TR: If it were to turn out that there's [a strategy for QuestFour where you always win], would it be correct to assume that wouldn't really bother you so much because your main purpose is to teach spatial reasoning more so than have a game with a deep strategy in it?

RB: That's interesting that you say that. There's actually a couple versions of the game. The first version of the game you're allowed to rotate the boards clockwise or counter-clockwise. That's to help you learn the mechanics and help build up your spatial reasoning. And there is an always-win strategy specifically for that version. It's kind of like the "deadly triangle" in tic-tac-toe.

TR: [If you get an X in three of the corners you have multiple ways to win in the next move.]

RB: Exactly. The same thing happens in [the "rotate in either direction" version of the rules] where if you have two of your pieces on one board in a row and then you put one piece on an adjacent board you can rotate left or right, put your other piece there, and you can win. It's unblockable. The second version of the game is where you can only rotate clockwise forcing you to think 4, 8, 12, 16 moves in advance. In that version of the game, I've not found a guaranteed winning strategy. Because someone can always [muck up] your strategy by rotating a board away from you or blocking you with their own piece. I'm not saying there's not one but I haven't found it yet. I don't think [QuestFour being a solved game] would bother me because ultimately what I was more interested in is something that's gonna make you think and something that you can have fun with.

This is where I usually say "I'd like to thank Robert Brown for taking the time to speak with me", but there's a bit more to this story beyond a conversation we had on the phone. Robert insisted that I should actually play his game to have a better understanding of it and so he offered to come to my city and meet me. I invited him to my home, and we spent around two hours talking about the game as well as playing it.

My first impression of the game is that it absolutely delivers on its promise of working your mental muscles in regards to spatial reasoning. The first game was played with the"rotate in either direction" rule-set and ended in a stalemate. I pretty much got my butt handed to me in every game after that, and I was being quite cautious about trying to keep Robert from being able to line up a winning move.

You have to juggle thinking several moves ahead along with the knowledge that there are three distinct ways to win as well as one quarter of the board rotating every turn. I brought up the idea of "tempo" - don't get too caught up in what your opponent is doing or you'll lose the initiative and control of the board.

At the conclusion of the play session, I walked Robert out to his car and thanked him for taking the time to drive over an hour to visit me. I understand firsthand why he wanted me to play the game and why he's had such difficulty with the rules. It really is quite difficult to grasp everything that's there until you actually get your hands on it, and now that I have I can say that I'm very anxiously awaiting the launch of this game so I can pick up a copy for myself. Aside from being a great educational tool, QuestFour will be a worthy addition to any board game enthusiast's collection.

Robert Brown has provided us with a print and play of a simplified version of QuestFour in a 2D setting which you can download here. QuestFour was nominated for Playcrafting's 2015 Tabletop Game of the Year, and you can follow QuestFour's development progress on Facebook.

All of the images in this article were provided courtesy of Robert Brown.

Educational games don't have to be boring - what fun educational games have you played? Are there any other board games you like that exercise your brain? Tell us in the comments below!

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net