From your bird’s-eye view, you see it: a sea of ghosts and grunts, all full health, blocking your path to the exit. The rest of the party is behind you, ready to strike at a moment’s notice. The bravest of you, Thor, is carrying the final key. Your stamina wanes slowly, your stomach growls for food. You will need some if you are to survive. You give Thor the order, and the barbarian brandishes his axe as he unlocks the door. The monsters pour out, as you and the party do battle for what may be the last time ...

The above is just a taste of an experience many fans have been through before. The overwhelming odds of a horde of monsters coupled with the camaraderie of party members to help you through the ordeal without dying is the core experience of the dungeon crawling sub-genre. Be it first-person, third-person, co-op, or single-player, dungeon crawlers are a seminal favorite of many for their strategic play and crushing difficulty.

Many great games in the world of role-playing have come from dungeon crawlers in one form or another. Some of the most seminal works would be Diablo by Blizzard, the Wizardry series, and the Advanced Dungeons and Dragons games. But one game is often overlooked for its contributions both in and outside the gaming industry, let alone what it contributes to role-playing. It is a game that was able to transcend its somewhat awkward design and pave the way for the likes of Diablo, Torchlight, and countless others who follow in their footsteps. That game is the arcade classic Gauntlet.

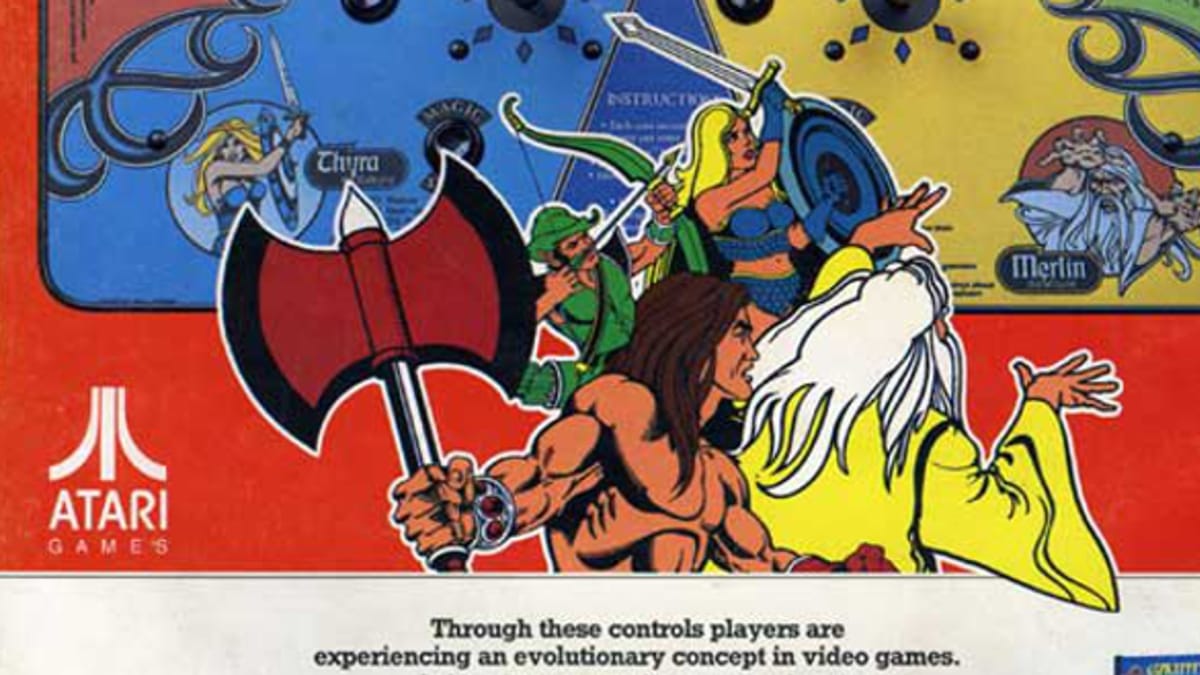

Developed by Ed Logg, the co-creator of arcade classics Centipede and Asteroids, Gauntlet would be a landmark for the Atari Corporation as one of the first four-player co-op arcade titles, eschewing the standard single-player or two-player competitive slant that most arcade games had at the time. It was a massive undertaking that could have failed miserably, and almost never came to pass. Gauntlet would also be one of the first mainstream role-playing games to offer multiplayer and party dynamics, a form of role-playing that is steadily growing in popularity.

“Gauntlet came into an industry that was dominated by player-versus machine experiences like Space Invaders,” states Jeremy Saucier, the assistant director of the International Center for the History of Electronic Games during an interview with Polygon. “There was some two-player but the standard was one person playing for 25 cents per game.” During the 1980s, Atari and other companies began to experiment with more sophisticated arcade machines, but they often failed due to the price of play. With 25 cents being the standard, games that were 50 cents or $1.00 were rarely a success.

Logg discussed this aspect of the game-making process at the 2012 GDC, as well as the basics of the arcade economy during its heyday. "The street locations by 1985, basically you didn't sell anything into them, it was all used games. And the reason for that is the street operators actually split the earnings from the game with the location. So if you earn $100 a week, the operator gets $50 and the guy who owned the location would get the other $50.

So it was very hard to get a return on investment on a game you probably paid $2,500 for." The coin-op industry was at the time sagging heavily, as Logg suggested because distributors were reluctant to take on new machines.

These poor returns after price increases on more complex games primarily resulted in failures across the board. For some statistics, the average player was expected to play for 90-180 seconds or two minutes per quarter. Because of this, Gauntlet’s design became a critical shift in the arcade industry, one that allowed four players to deposit .25 cents a turn, meaning an average game of Gauntlet could net $1.00 every two minutes. This allowed for not only a steadier cash flow but higher return on investment for operators and location owners.

Logg first conceived of the game Gauntlet through two sources. First was his son, a huge Dungeons and Dragons fan, who brought the idea up to make a D&D-style game for Atari. The second source comes from a game called Dandy, first made for the Atari 800 (or Atari 8-bit) and later ported to the 2600 under the title of Dark Chambers.

Dandy was among the first top-down dungeon crawl games ever made, and one of the few multiplayer games that followed what we now know as the classic Gauntlet design - two players traversing a maze-like dungeon, fighting monsters, destroying generators, and collecting treasure and food as they rush for the exit.

Dandy and Gauntlet shared many similar design mechanics, but Logg implemented major differences that would become hallmarks for the Gauntlet series. Food, which could be collected and used at any time in Dandy, was used immediately in Gauntlet. Gauntlet also slowly decreased your health as time went on, a mechanic designed to give a sense of urgency to arcade players while adding cooperative elements while playing. Finally, the characters were designed to have different strengths and weaknesses in Gauntlet, including speed, melee power, magic power, and defense, while in Dandy the four players were the same in terms of power, speed, and ability.

The similarities were so great, that Dandy’s creator, John Palevich, took legal action to ensure that Dandy would be a protected copyright after he discovered the similarities between the two games. Among his demands, Palevich wanted to be credited as a lead game designer on Gauntlet, despite never working on the title himself. Atari declined this request back in the 1980s since adding his name to the credits would change the ROM’s configurations and be too expensive. The terms were settled amicably, however, with Logg giving full credit to the influence of Dandy on the creation of Gauntlet.

The changes made to Gauntlet also helped with a primary design issue that Logg was faced with: how do you keep players playing? Logg implemented several firsts for Atari, from voice chip technology to include a “narrator” for the players, and extra large panels screens in medium resolution to compliment four players at a time, to fighting with Atari managers about including a personal memory device (PMD) into the machine to save progress for players. All of this made Gauntlet contain some of the most complex hardware of any arcade machine in the 1980s. Atari almost never released the project, believing it would be a failure as a cooperative machine. The game began development in 1983 but would be delayed for two years, partially due to layoffs incurred by the North American Video Game Crash, and partly due to the funding being delayed as Atari's finances were in flux during their gradual decline.

From a financial standpoint, Gauntlet was a huge risk. The extra hardware for voice synthesizing, the inclusion of a PMD for progress saving, and even the size of the monitor screen and video presentation made the title very expensive for Atari. Smaller things, such as the in-game resolution, were also financial decisions to keep track of. Dennis Scimeca of G4TV states: "Medium resolution was coming into vogue and there was a large push to use it, but arcade operators were resistant as they purchased the machines from manufacturers like Atari, and medium resolution monitors added an additional $300 per unit. The choice was between 19” and 25” monitors, but the latter cost an extra $100." This would turn Gauntlet into one of the most expensive titles for the arcade industry, at a time when most in the industry were cutting costs.

It would be a team of eleven, including artists, engineers designers, and technicians, who would create the Gauntlet machine we know today, complete with the sound chips, scrolling levels, and the extra-large cabinet and monitor design to accommodate four players. Atari was still dubious that the game would work. “The marketing department said that would never work,” said Saucier. “They questioned whether you would get four people, who did not know each other, to play together. But when Atari put this game out to test, it performed very well. It proved that people who did not know each other would play together.”

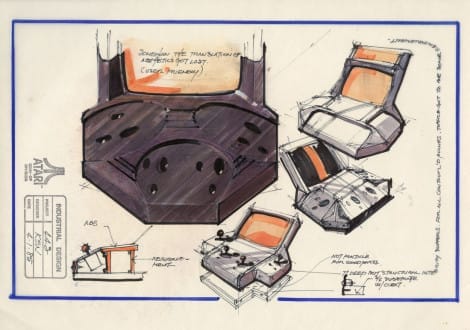

The game's design became a major sticking point, one that Saucier believes created a logistical problem for cabinet makers at the time. Saucier recently acquired a collection of design documents from Atari that pertained to Gauntlet, documents that were released and reported on by Polygon in 2013. “When you look at some of the documents, you’ll see problems like how you get four people together at a machine and actually be able to see everything,” he said. “Problems like shades and glare, angles of view. You are dealing with design issues where if you fix one thing it creates another problem. This collection illustrates how much went into these designs and how creative this process really was at that time.”

Despite the logistical “problems” from a design point of view, the field tests proved to be very successful, with Gauntlet making more money than arcade stalwarts like Donkey Kong and Pac-Man at the time. Logg even had to pull a test unit from an arcade because SEGA attempted to photograph the machine, likely interested in the design specifications for their own games. Focus groups were also conducted, with some admitting to spending upwards of $50 on a single Gauntlet machine in a single session. Overall, Gauntlet would ship 7,850 copies in the United States alone and another 3,750 worldwide. As a comparison, one of the top-selling Arcade titles by Atari in 1985, Temple of Doom, shipped only 2,800 units.

Gauntlet as a series can also be marked not only by its innovations as an arcade game but also by its longevity as a concept. The primary design choices of Gauntlet reflected the need to cooperate as a team, which laid the foundation for imitators and disciples worldwide. I mentioned previously games like Diablo and Torchlight as primary examples that borrowed from Gauntlet, but other games from different genres also carry on Gauntlet’s core design strategy in new ways. Modern games like Left 4 Dead, Fuse, and especially Borderlands expand on the dungeon crawl genre in new and surprising ways, trading the fantasy-themed aesthetic for something different, but keeping the core elements of working together as a primary mechanic, and in the process showing different layers to what a role-playing game can be. In a sense, the design philosophy behind a cooperative game can be traced back to Gauntlet, as it was the first to successfully transcend co-op play into mainstream success.

Through all of this, Gauntlet has stood the test of time as one of the true innovators of the gaming industry. Since its release 30 years ago, the series is still producing titles, cementing the franchise as one of the few arcade classics to constantly reinvent itself with each generation. Gauntlet’s legacy is one of engineering innovations, daring to try something new that was against the norm, and in turn, creating one of the oldest and most memorable co-op experiences in gaming history. Over time it has morphed into one of reverence for design, with many iterations of the core tenants of what made Gauntlet amazing in 1985 still in practice today. Through and through, however, Gauntlet is just another example of how adaptable and innovative role-playing games can be, offering a unique take on the genre that has stood the test of time.

This post was originally published in 2015 as a part of our Playing Roles series. It's been republished to have better formatting.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net