From their roots as either guided storylines on consoles, to dialogue selections on PCs, role-playing games run the gamut in showcasing choice and consequence through dialogue and action - do you go to the left or to the right in this dungeon? Do you chastise or help a beggar? Each of these actions is a role-playing choice controlled by the player and often helps shape the player's experience as a whole.

RPGs have followed such actions as a primary gameplay feature, but it was only recently that the art of conversation has become a part of the character’s overall growth. For years, RPGs have used this trope to help flesh out characters and worlds, all done with text and interaction through selected dialogue scripts. Some games, such as Planescape Torment, bring it to a whole new level with the detail and interactivity of the world. Others, such as the Elder Scrolls series, used dialogue as a means to an end, a tangential part of the role-playing experience.

All of it, however, had unifying features; it was silent, scripted works where the player makes all the decisions. This changed, however, in 2007 when BioWare’s Mass Effect came into the picture.

Featuring the first of its kind for an RPG, a fully voiced protagonist where you can control most of your dialogue options, Mass Effect, and its conversation wheel, was an important, if somewhat controversial, addition to the role-playing experience. Important, because it helped modernize the RPG, controversial, because many believe it helped destroy it.

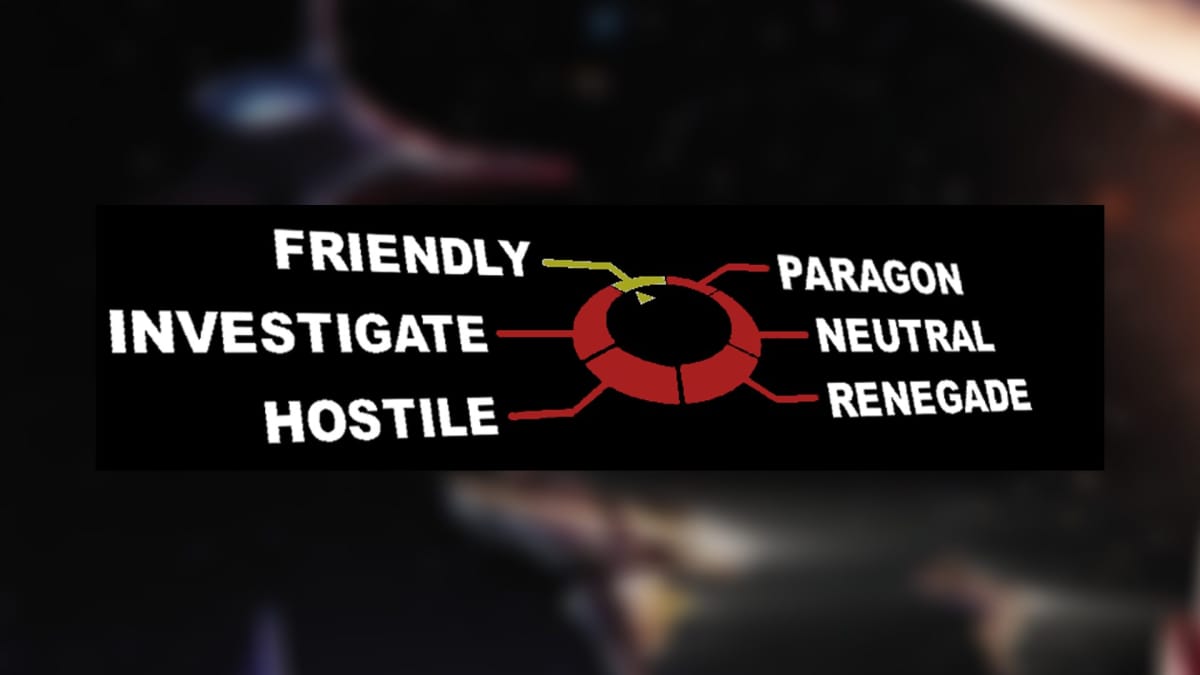

The wheel concept is simple to understand. You have several dialogue choices along the wheel, one positive, one negative, and one neutral. The wheel also sported an investigative option from time to time, and special dialogue options based on your morality, in the case of Mass Effect, Paragon and Renegade choices. BioWare also placed dialogue options specifically on the wheel; the top right was always the “kind/diplomatic” choice, while the bottom right was the “aggressive/nasty” choice.

In effect, the wheel would attempt to simulate the questions and tone of a conversation, having the player character, in this case Commander Shepard, to speak dialogue to characters in an attempt to keep conversations flowing. The innovation of this was a more interactive world filled with talking NPCs that you can glean information from, or simply ignore outright, adding more layers to your character’s role. With players being subtly trained as to which option is where, the Pavlovian response to be diplomatic, aggressive, or neutral becomes second nature - you don’t know what you will say, but you know how you will say it.

This is the dialogue wheel's greatest strength in the end: controlling tone. Many have cited the problem with the dialogue wheel was that tone would be inconsistent with the character, and while in some extreme cases, most notably in Dragon Age II, this can be argued as true, the tonal shifts also add another layer to characters by showcasing the gamut of emotions-or how realistic people would act in such situations. If someone is criticizing you, you could instead act aggressive towards them, then shift back to diplomatic when they get the hint.

Tone also gives each conversation texture to it; it provides feedback to players how NPCs would react to your character, in effect giving you direct feedback of their response and possibly intention.

Of course, it’s not perfect, as tone can also get in the way of role-playing when it goes against the intention of the player. One of the flaws with the dialogue wheel was that lack of indication for tone, which BioWare has continuously updated the design to add more tonal options. The wheel’s insert, for example, showcased tones and a wide range of emotions in Dragon Age II and Dragon Age: Inquisition. Inquisition also further updated the wheel, by making big-ticket choices glow to inform players that this choice is important, and even explains what the choice will do in a small pop up box. This was designed to remedy complaints about the wheel - namely players feel they don’t fully control their characters and their words.

And, they don’t in the end. Where the dialogue wheel becomes controversial is the belief by some that it takes away role-playing nuance of our choices. The wheel creates a disconnect between characters and the player, some argue, because the character is no longer fully controlled by the player; their actions, beliefs, ideals and motivations are scripted completely, which creates a hybrid character that is both the game's and the player's.

The wheel, in essence, represents the “dumbing down” of RPGs to some players, as the paraphrasing system offers less choice and control of our character’s actions, sometimes making them simply binary in their function.

Of course, most modern RPGs work this way, with or without the wheel as a mechanic. More and more, role-playing games have been adopting the wheel design for their dialogue system, but not the nuance or the additions that BioWare has added to make it more effective for their new, cinematic style of role-playing. Titles like Fallout 4, Deus Ex: Human Revolution and even the Telltale Games all employ a dialogue wheel style, which helps with their current, cinematic approach for streamlining their games.

However, the results are mixed; Deus Ex still offers decent role-playing challenges, while Fallout 4, many argue, strips away too much of what made Fallout a beloved RPG. Other games that don’t use the wheel, such as The Witcher, function the same way in the end, using a paraphrase/tonal system in conjunction with a more "classic" listing of dialogue options.

The reason for it is both practical and streamlining. Practical in the sense that it can control the amount of dialogue and choices presented in games, as word budgets are sadly a determining factor of how much a character can speak in AAA RPGs. In effect, the wheel streamlines conversations because it allows for near seamless interaction with the world around you, despite arguably saying less.

This does, however, mimic the brevity of real world speech, but for many RPG fans, the writer was often king, so the more descriptive, more grandiose your words were, the more popular you became.

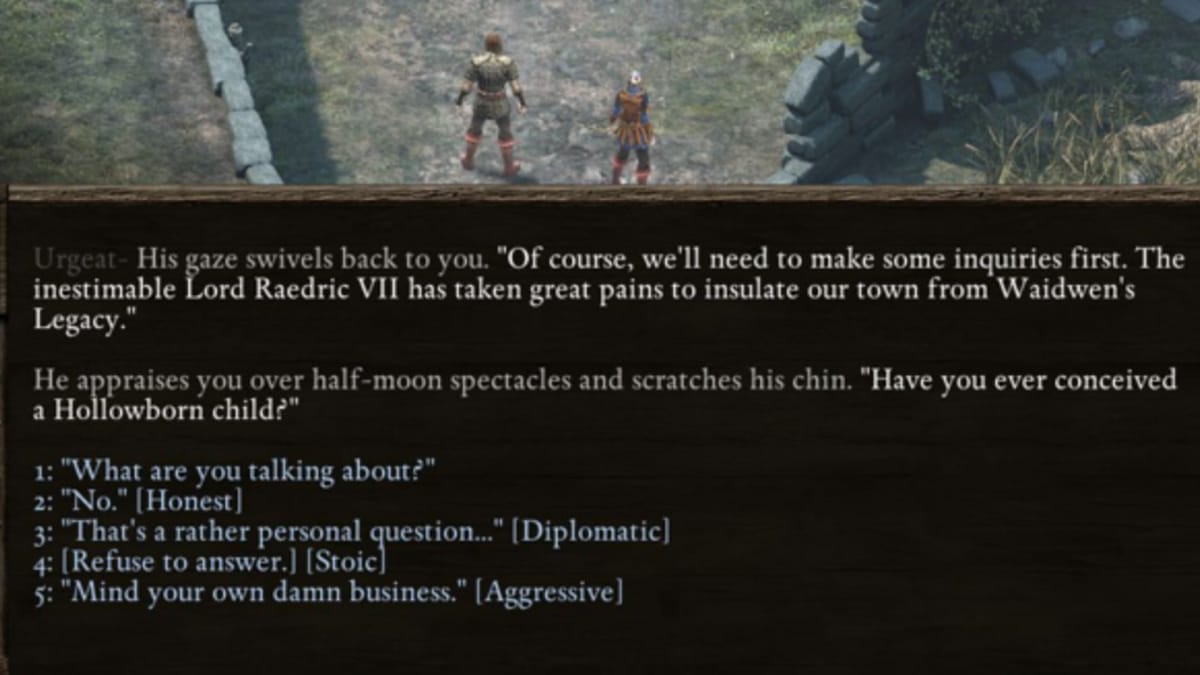

Much of the criticism against the wheel is nostalgia for what was once found in the CRPG space - games with specific dialogue completely scripted. Some modern titles, such as Pillars of Eternity and Shadowrun Returns, have attempted to revive that tradition in a smaller scale, eschewing the more cinematic approach modern AAA RPGs have been following since 2007, and have been minor successes for their niche. However, even in those games, the tonal aspect of the wheel bears influence. Pillars of Eternity, for example, allows players to showcase tone of speech, so aggressive or clever responses are marked as such if the player keeps that toggle on.

This is not dumbing down content though, just as the wheel isn’t - it is pushing the content forward for a larger audience. It is the difference between a cinematic approach and a novel approach - both are catering to similar audiences, but one would prefer to read and carefully control their actions, while others would rather listen and carefully respond to what they hear. Both, in the end, offer strong role-playing choices, big and small, that provide the player with what they want: a RPG experience.

The true innovation in the end for the dialogue wheel was how it allowed players to become more attached to their characters through that experience - to help in shaping how they react to the world around them and to guide them on a journey that for many was more personal than silent, scripted dialogue. That direct feedback given through dialogue is immediately gratifying for many, and in the moment can become an amazing scene of seamless ideas, both old and new, making something great if it fires on all cylinders.

This hybridization in the end can be an asset. After all, console role-playing games like Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy have remained successful due to gameplay with a fixed protagonist beyond most control. BioWare, CD Projket Red, and arguably Square Enix and Bethesda have moved beyond such labels, offering a new experience—this cinematic experience of role-playing to the player. The dialogue wheel was first the step of that change, and the constant updating seen by BioWare shows that the wheel itself is a growing, changing mechanic catering to the tastes of this audience.

Very few gameplay mechanics have helped in shaping a growing change in a sub-genre of video games before. For that reason alone, the dialogue wheel is an important, if pivotal, junction point in the history of RPGs. For good or for bad, the wheel represents this new approach, while still remaining true to its function to deliver a role-playing experience through dialogue in a way never thought possible a generation ago.

This post was originally published in 2016 as part of our Bullet Points series. It's been republished to have better formatting and images.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net