The controversy surrounding the Valve ‘Paid Workshop Mod’ incident has sparked a great number of discussions within the PC gaming fanbase. Terms such as ‘greedy’, ‘entitled’, and other condemning words have come from all groups engaged in the debate. The two objective truths in all of this chaos are the large 75% cut of the earnings split between Valve (30%) and Bethesda (45%) while the remaining 25% goes to the modder and the genesis of a ‘some modders are more equal than other modders’ paradigm. The backlash from consumers stopped this plan dead in its tracks in very much the same way that the Xbox One DRM was killed before its launch in the Summer of 2013. This article isn’t about the ethics of the consumer response; instead it is about the legal can of worms that would have been opened if Valve had proceeded with the plan.

“Valve has finally solved the technical and legal hurdles to make such a thing possible [paid mods], and they should be celebrated for it. It wasn’t easy. They are not forcing us, or any other game, to do it. They are opening a powerful new choice for everyone.” - BethesdaAt surface value, Bethesda’s official statement on paid mods seems innocent enough. Here’s where things become tricky, though: the legal hurdles in creating monetized mods would be continuous rather than a single obstacle. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 Sec 103 definition of infringement includes this line, “ Prohibits… manufacturing or trafficking in technology designed to circumvent measures that control access to, or protect rights of copyright owners in, such works.” A strictly literal interpretation of this statement would seem to condemn all of modding altogether. Regardless of how the judicial system eventually rules the legality of modding, there remains the issue of copyrighted works and assets used in monetized mods. Anyone who has used mods before already knows about the multitude of potential copyright infringements entirely possible within Valve’s own game library.

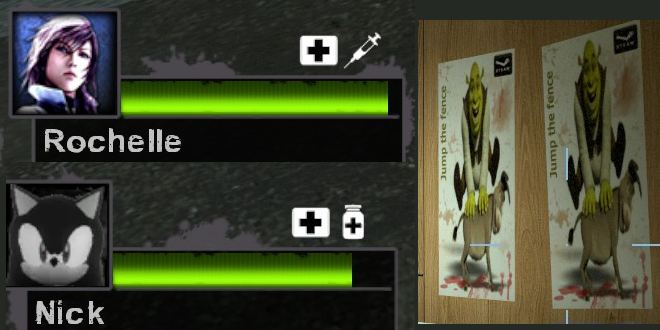

All of the texture mods seen in this screenshot are readily available on the Left 4 Dead 2 workshop for free as of the posting of this article. If Valve were to attempt monetization of these mods, then Sega, Atlus (now a division of Sega), Square Enix, Hasbro, Capcom, Dreamworks and Scott Cawthon (creator and owner of Five Nights at Freddy's) would need to authorize each mod. The process itself includes the IP holder determining their payment ratio and deciding whether or not their intellectually property is being properly represented in accordance with their vision. Sheer absurdity is often the best way to punch holes through unsound business models. The reality of this situation would be that maybe a few mods would be "legitimized" while the vast majority would either remain free or removed through cease and desist orders. This isn’t even delving into the topic of add-on campaigns that use outside elements.

What then is keeping these mods alive amidst a sea of ambiguous copyright? According to Ryan Wallace of the BYU Law Review, the terms of the EULA are the reason.

Additionally, along with the official modification tools, game creators typically include an End User License Agreement (“EULA”) that expressly grants consent to allow video game users to modify their games. However, the EULA also typically signifies that any user-created content is property of the original developer and, therefore, cannot be sold by the modder.” [Page 229]An increase in the longevity of content generation for a game, no matter how absurd, tends to generate more sales of a game in the long term. This approach is why such games as Star Wars Battlefront 2 and Vampire: The Masquerade: Bloodlines are able to survive long after Windows compatibility issues would have killed the games for good. It is impossible to make a broad statement pertaining to all companies that may have their work infringed in mods. However, it is fair to say that many companies are unlikely to sick their legal teams on individual cases of unpaid mods. (Barring extreme cases of negative publicity along the lines of the infamous Hot Coffee mod for Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas)

Fan games that run on an existing game engine or use existing assets, fall into a category of copyright infringement that very often results in C&Ds, if not worse legal implications. Fan games such as Streets of Rage Remake, various , and even a Metal Gear Remake (Konami authorized it until they changed their minds) were all C&D’d at some point during development. These projects, no matter how noble in their intent, are almost always doomed because the original IP owners can’t show a moment of weakness with their copyrights. Companies want to retain control over their property for as long as they can to avoid their work falling into the public domain. This is why derivative elements are necessary in games such as Freedom Planet, (Originally a Sonic the Hedgehog fan game) Mighty No. 9, and the recently revealed Bloodstained.

Simultaneously, these games don’t run on game engines that the IP holders own exclusive rights to. This is a crucial distinction that separates a work from being seen as nothing more than a ‘romhack’ before the law. That’s not to say there can’t be legal ramifications for improper use of ‘freelance’ engines such as Unreal because an improper licensing of the Unreal 3 engine for Too Human resulted in Epic Games suing Silicon Knights.

How about games like DayZ, Counter-Strike, Defense of the Ancients (DotA) or even the original Quake mod Team Fortress? Why have they thrived in spite of being, at their core, ‘fan games’? The answer is quite simple: the popularity of these mods led to publishers ‘legitimizing’ them as standalone releases. DayZ, the most popular mod for Arma II to this day, prolonged the life of the 2009 base game to such a degree that the developer Bohmeia Interactive is working with Dean “Rocket” Hall to release a full standalone version to supplement the modded version. The origin of Team Fortress Classic dates back to Valve converting a Quake engine mod to run on their GoldSrc engine. Valve later hired Counter-Strike creators Minh Le and Jess Cliffe in 2000 due to the success of the legendary 1999 Half-Life mod. DotA 2 is the first example of a major ‘legal conflict’ over a derivative of a mod because Valve’s attempt to franchise the IP intruded on Blizzard assets. Under the EULA agreement, DotA was Blizzard’s property since it was an alteration of Warcraft III. One would think that Valve would see the issues inherent to paid mods operating within existing IPs, titles and engines.

All of this said, should modders be condemned to doing everything for free? Paid content production structures are already in place for games like Team Fortress 2. The process from ‘concept to cash’ is simple enough: create, test, moderators choose and test the mod and then, finally, profit. There seems to be a bit of hypocrisy in supporting this structure, but it is almost a necessity in a multiplayer-only team-based shooter with sporadic drops, rabid trading and its own marketplace. Free mods for TF2 exist, obviously, primarily in the form custom maps and ‘unofficial’ skins.

The subjectivity of desire for new hats, weapons with different stats and abilities, and other novelty items drive the demand for items in the marketplace while the dropped items help to create supply. People who don’t want to pay for marketplace weapons will get drops for playing, thus everyone ultimately seems to benefit from the system. The free market determines which multiplayer content rises to the top and which content fade into obscurity. After all, it isn’t as though they are charging fixed prices for mods in single player games like Skyrim… Oh wait…

“There are certainly other ways of supporting modders, through donations and other options. We are in favor of all of them. One doesn’t replace another, and we want the choice to be the community’s. Yet, in just one day, a popular mod developer made more on the Skyrim paid workshop than he made in all the years he asked for donations.” – BethesdaThere is no clear answer to the question of whether or not creators of primarily single player game content should be directly compensated for their work. An answer leaning either way would invariably strike a nerve with factions of the modding community. In many ways, mods are the modern version of the ‘unofficial’ expansion packs from the '90s for games along the lines of Wolfenstein 3D, DOOM, and Duke Nukem Forever. Digital distribution has all but removed the conventional ‘expansion pack’ model in favor of quality controlled downloadable content. In this vein, mods can be classified as ‘unofficial DLC’ because the term encompasses cosmetic, gameplay and story additions to a base game not released from the official development team. In the case of the ‘The Sith Lords Restored’ content mod, an ‘unofficial DLC’ package adds missing content to Knights of the Old Republic II: The Sith Lords. Although the scope of the modding community varies drastically from major projects to small bug fixes, there is a common enthusiasm that unites them all.

What paid mods would do is create an Animal Farm-like hierarchy with some modders being more equal than others. Mods have always grown organically through word of mouth; creating a monetized mod at inception would likely only succeed in creating a palace cracked atop an asymptote of isolation. Content creation can be a time-consuming effort, no doubt, with many loopholes to potentially jump through. Free distribution of a mod has the potential to grow into something major while the ‘fee’ model stunts the capacity for expansion.

Not to dismiss the concept entirely, rather to highlight the passionate nature of the community, but overall, modding is an elaborate form of fan art that relies on the ‘fair use’ defense. People make mods in an effort to improve and add to the experience of a game. The voluntary nature of modding means that someone going vanilla and another person with a crazy amount of mods are able to have the same level of enjoyment from an existing game. If someone thinks that fighting Thomas the Tank Engine dragons in Skyrim is a good idea, then there should be nothing to stop them from making what they enjoy. As the Bethesda press release says, Patreon and other similar sites allow for fans of individual modders to donate to their work. Besides, if someone wants to profit off of Steam, then they can always use Steam Greenlight for their original content.

Note: All legal interpretations in this article, unless otherwise sourced, represent an amateur interpretation of Copyright Law. If you or someone you know is in a position of requiring legal advice, turn to the services of an accredited copyright/intellectual property lawyer.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net