On March 23rd, New York City’s own Playcrafting hosted their Women in Games themed night of Demo & Play in honor of Women's History Month. Featuring a plethora of developers and industry professionals, the evening kicked off with a showcase of five different games, developed by women, followed by a panel of women discussing what it's like in the indie game industry, followed by a Q&A session with the panelists, ending the night with networking and game demos of each of the five previously showcased. Featuring incredible diversity and women with very different experiences in the industry, the event was certainly not one to be missed.

The first of the games showcased was Lee Ling with Box Fighter 2000, a PvP game that can have up to four players. Developed by a two person team on the Unity engine, the game is still in its early stages; however, it was available for demo. Using teleport mechanics and a set game board, the players face each other playing as literal boxes, each attempting to take the other out, similar to paintball. The game uses teleport mechanics and was described by Ling as being similar to chess, as the game board forces you to think about strategy and tactics rather than straight attacking your opponent.

Next was Someone Has Died presented by Adi Slepack and Liz Roche. This inventive card game involves lots of improvisation and revolves around the estate of a mysterious dead person. Cards are dealt to each player, which describe their background and relationship with the dead person, and the estate is overseen by an Estate Keeper, much like a DM in Dungeons and Dragons, whose job it is to keep order and ensure the game progresses smoothly. The game progresses for four rounds before it is decided who has “won” the game and has the best claim to the fortune. Also developed by Ellie Black.

ASD by Sarah Granoff is a short but sweet game that shows how video games can be used for more than just a fun diversion. ASD, standing for Autism Spectrum Disorder, follows a short day in the life of Lucy Garvey, a woman on the spectrum. The game shows the struggles and difficulties of living with ASD, such as when minor inconveniences for people not on the spectrum can be much worse for someone who is. Developed by someone who is on the spectrum, the game attempts to show the unique struggles and make it much more understandable and relatable to the average person, as video games have a “unique capacity for empathy as a storytelling medium,” according to creator Granoff. They can be used as tools for education and understanding, awareness and acceptance. The game is currently available for download on itch.io and was originally a student project at NYFA. Future version of the game are planned to include a greater variety of settings and challenges for the player to overcome.

Fruit Warrior MR, developed and presented by Adina Shanholtz, works with Microsoft’s HoloLens in mixed reality, hence the MR in the title. While the HoloLens is worn like a virtual reality headset, it’s defined as mixed reality, due to the headset mapping the surroundings of the room and allowing you to interact with it in real time using gaze, gesture and voice. Fruit Warrior is a relatively simple game designed to introduce users to mixed reality and has the goal of collecting all the pieces of fruit in a set amount of time.

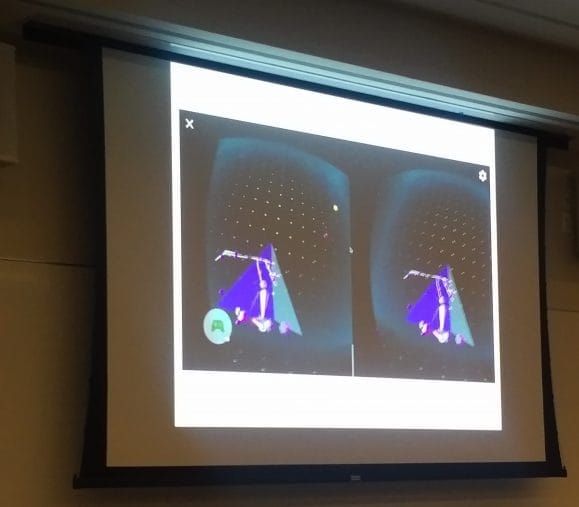

The final game to be shown was Mind Roomie VR, designed by Maria Mishurenko, an independent developer from Brooklyn. Using a VR headset, the game aims to teach both children and adults the basics of mindfulness. Unusually, Mishurenko stated that there is no right or wrong way to play the game. The intended goal is to remove all of the “branches” from the head of the roomie character and in doing so, remove the noise and gradually achieve a state of calm and peacefulness. However, if your personal preference is to have as much noise in the game as possible, that’s an equally valid way to play. The game uses the Google Daydream controller and uses colors and thoughts to customize the game experience to each individual user. Each session of the game takes approximately five to eight minutes, and future versions are planned to include more feedback loops.

After each of the games was demonstrated, there was a panel discussion of women in the game industry, moderated by Tatiana Tacca. Panelists included Adelle Lin of Code Liberation, A.V. Perkins of University of Dope, Laila Shabir of Girls Make Games, Margaret Robertson of Playdots and Sande Chen, a WGA Award and Grammy nominated writer and game designer. The first topic of discussion was about the challenges that indie developers face when trying to make games. Shabir was the first to speak up, stating with the outlook that many still think making games is not a thing women or girls do, it’s still seen as a much more masculine pursuit. Add to that the challenges of amassing resources for development, which Perkins added to with the point that sometimes the actual techonology and technological challenges can be the hardest part, which is part of the reason why her current project uses a blend of cards and interaction in technology to bridge the gap between the two.

Chen’s talk of indie developers lacking in marketing segued into the next topic. What are some tools and techniques indie developers can use to market their games effectively in what can be an oversaturated market? Robertson was the first to point out that marketing can be done on a budget, while Perkins added that a previous online following, such as a blog, can be used to leverage following. All agreed that it’s important to use connections and that word of mouth still works as a viable marketing strategy. Facebook ads and social media are also effective. Shabir, with her experience designing an educational game, pointed out that you also need to target your audience effectively, and Chen chimed in that YouTube can be a very valuable resource. Don’t be afraid of using non-traditional outlets to find an audience, such as taking out ad space in a literary magazine for a poetry video game. Untraditional? Yes, but effective as well.

Next the women talked about where their inspiration for making games comes from. Games can come from anywhere, said Chen. Inspiration can commonly come from everyday life, a point which Robertson agreed with. Lin suggested drawing from personal experiences, fears and anxieties, use the game as a point of emotional connection. Robertson also added that games can be based on anything you do, a moment of remembering or internal things. Perkins freely admitted to using media for inspiration, explaining how the Netflix show The Get Down was instrumental in designing the logo for University of Dope. Shabir also suggested using childhood experiences and learning through context and day to day life.

The topic of gaming narratives was next, and all the panelists agreed that indie gaming narratives can sometimes feel very shoehorned in as a result of developers making the game first and then realizing they had to add a story down the line. Chen, as a result of having years of writing experience, stressed the importance of bringing in a writer early in development on a game so that you can know your story as you make the game. As content can take a long time to generate and design, knowing your story as a part of the gameplay and environment, or even if you want to have a story, can add levels of engagement and motivation to the game. Chen also added that the story is best brought in when it merges with gameplay as you don’t want to force the player to do something counter to the story; for example, having the mechanic of collecting coins in a game where the main character was raised by tigers. The best experience, she said, is when art, program, design, and writing all grow organically together.

Even for a company like Playdots, which is not known for deep and complex narratives, Robertson admitted that there is a dark, terrible secret at the heart of the story. But, as she also pointed out, you don’t have to have a story in a game. If you are, ask yourself why. A completely valid answer is that there’s a story you want to tell or context you want to add to a game, and if you know why you want to tell that story, you can make it as small a story as you need to fill that space.

Next the panel talked about gaming trends. Lin was particularly enthusiastic about the trend of interesting narrative games such as Ladykiller and others with various gendered sexual experiences, as well as Nina Freeman games, which opened up difficult to talk about stories. Perkins admitted to liking the nostalgia trend, which particularly calls back to 90s culture and is seen across all media platforms, not exclusive to gaming.

When asked about how to educate people about gaming and what people are doing to get their start in the industry, all of the panelists had helpful suggestions. Networking was agreed upon by all as a valuable resource. Perkins stressed the importance of networking and research, stating that it was how she herself found Playcrafting, and Shabir admitted that coding can be intimidating to those who have never done it before, but technology has made it a very accessible field and there are resources out there for those willing to learn. Resources like Girls Make Games and Stencyl are there to help, and she stressed that after you make your first game or project, it will feel much less intimidating. Robertson on the other hand, focused advising those to be realistic about their goals and where they want to be. Anything is possible and the scene is a thriving industry, but it’s a very different landscape if you want to make games for fun versus if you want to make a career out of it. Lin encouraged open mindedness and learning about the many tools available to game designers, reminding everyone that just because you know one tool is no reason not to learn another. Robertson agreed, but also discouraged “tool hopping,” as it’s important to finish what you started and learn what you have picked to use. Chen encouraged just getting straight to making your game or project, as the best way is to just jump right in and see what you can learn yourself and what you need other people for.

The panel was followed by a brief Q&A session and hands on demos of all games that were shown in the first half of the evening.