The Free Video Games Project has launched a free version of popular word game Wordle. According to the Project, Free Wordle has been released in order to combat the original Wordle potentially being put behind a paywall, which the Project views as a real risk.

What is the reasoning behind Free Wordle being released?

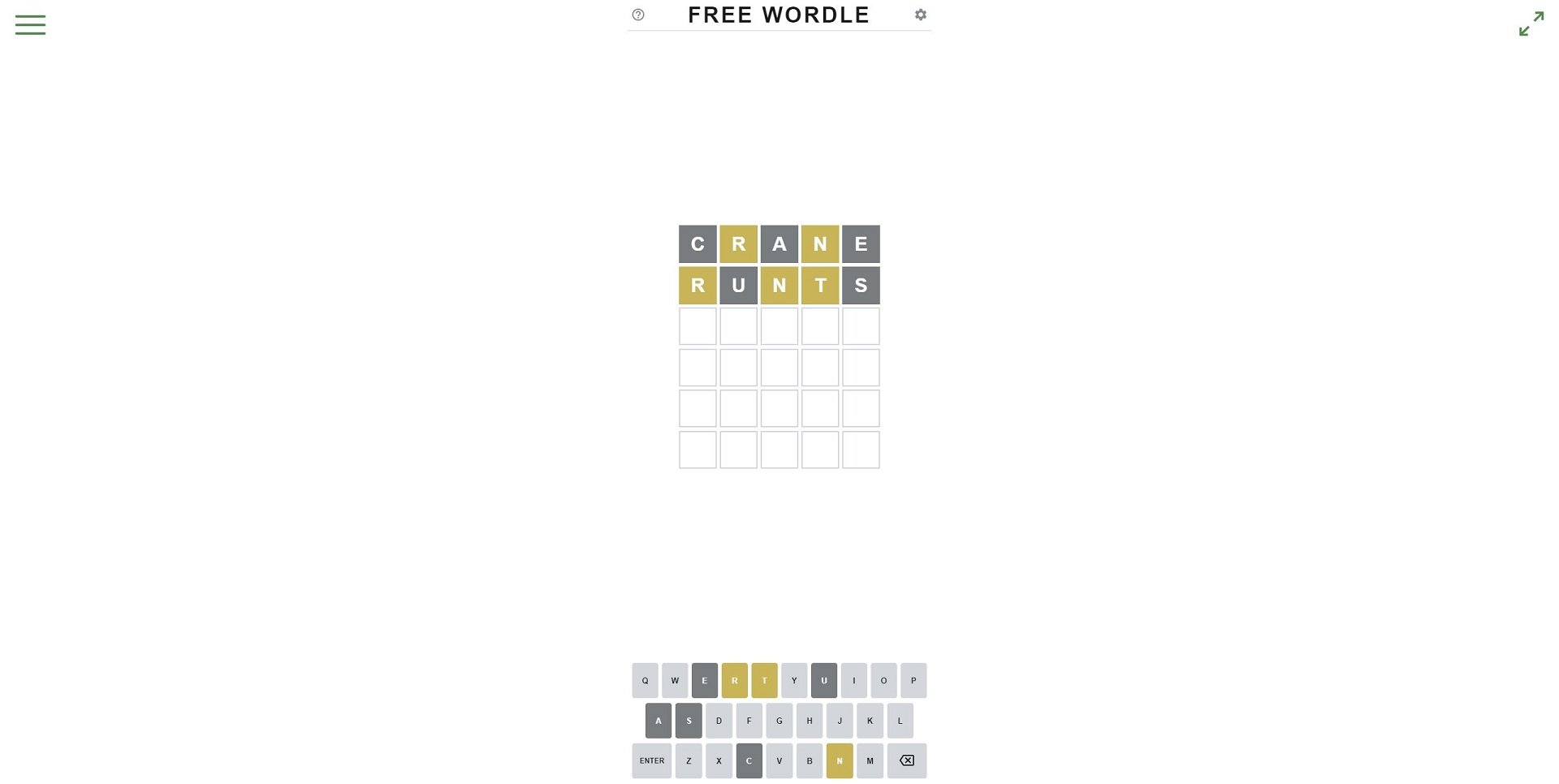

Game preservation is a massive issue for the medium, which is why platforms have sprung up to preserve games that would otherwise disappear or be forgotten. In the wake of Wordle's massive popularity, many clones and variants have sprung up, but Free Wordle is explicitly dedicated to preserving the original game as closely as possible. It looks practically identical to the original Wordle, with only the title header proclaiming Free Wordle to differentiate it. Otherwise, it's exactly the same game, right down to the keyboard aesthetic, six-guess limit, and colors for incorrect or improperly-placed letter guesses.

Of course, there are a few differences here. Free Wordle purports to be the first Wordle variant to offer a tool for importing history from other Wordle websites. This way, if you migrate to Free Wordle, you don't have to lose your streak. The site also offers the chance to track average number of guesses, which the Free Video Games Project says is "arguably a more useful metric" than keeping track of your score streak. Free Wordle is also available as a progressive web app for iOS and Android, meaning you can run it as an app on your phone or tablet with no download from an app store necessary.

Right now, Wordle is not behind a paywall, but the app was bought by the New York Times last month. The Times' subsequent comment that the game would "initially" remain free for everyone to play "spooked" the Project, according to spokesman Max Jenkins, who spoke to us via email. He says that Wordle, and other games preserved by the Project, are "at risk of disappearing" or not being made freely available online to play. Jenkins says that if the Times decides to keep Wordle free, he and the Project will be "thrilled", but that he's aiming to preserve it "just in case". Free Wordle was thus created by Jenkins himself alongside another programmer who prefers to remain anonymous. Jenkins says he chooses projects based on games that have "mass appeal", and that he'd be open to preserving games from stores like Nintendo's eShop if they close down, putting games at risk of disappearing forever.

What is the Free Video Games Project?

According to its website, the Free Video Games Project is dedicated to "preserving the very best classic video games, forever". Its site offers free versions of titles like Flappy Bird, Minesweeper, and Mahjong, with a view to preserving those games once their original versions become unavailable. The Project points to Adobe Flash; after Flash was discontinued in 2021, the Project says millions of games were "literally made obsolete and inaccessible overnight" (which has also led many platforms, such as Armor Games and Newgrounds, to attempt to preserve the Flash games that would otherwise be lost). Wordle is a slightly unique case in that it's not being preserved out of fears it will disappear, but rather out of fears it will become a paid product rather than the free endeavor the Project says it should remain. At the moment, the Project says it works on "just 1 or 2 games per year", although it hopes this number will increase.

Intriguingly, the Project features games on its website that still have active copyrights on their intellectual properties. These include Donkey Kong, Pac-Man, and Galaga, which are distinct properties and not simple ideas that can be cloned ad infinitum. Jenkins told us that the Project has "found IP owners to be tolerant if not altogether supportive" of the project, but that the outfit has a "war chest" in case it's needed. In the past, Jenkins says the Project has "brokered commercial settlements" when programmers have been hit with cease-and-desist letters, so it's not a situation with which he's unfamiliar. We also asked him about whether he'd like to see copyright law reform, and he had this to say.

It’s a good question and something we would like to see formalized more perhaps one day, although the law itself is for the most part fairly adequate. It’s more the practical aspects that often tilt the scales in favour of larger companies when they decide to go after an individual or small entity. It's well established that you cannot copyright a game idea or concept for example, and if someone recreates a game using their own code, then they technically own the copyright in that code. There are details that are important - sounds, words, characters, can all have their own copyright, and the issue of trademarks is an important consideration. In practical terms though, there is nothing to prevent a larger company threatening legal action, if they want to, regardless of merit, and this is a bigger problem, and more widely in society. These entities unfortunately understand that many individuals will simply fold at the first sign of legal trouble, or more often simply not have the resources to defend themselves. In some cases we are willing to advise people who find themselves in this situation, depending on the merits and our own circumstances at the time. Again, this is less of an issue these days, as the idea of independently archiving digital content for future generations to enjoy, gains acceptance.

The Project's efforts are part of a wider attempt to up the ante on preservation. There are concerns that companies like Nintendo and Sony are insufficiently concerned about keeping older games alive, so third parties are stepping in to attempt to preserve titles that they deem worthy of preservation. These include games like the Disney MMO Toontown Online, as well as an obscure Dragon Age web browser game titled The Last Court. Preservation is, of course, a legal minefield, but dedicated indie devs and curators are hoping that they'll be able to do their bit to keep old-school games alive and kicking. We'll bring you more on this as soon as we get it.