For much of its history, horror has been brushed aside as a trivial genre unworthy of serious artistic consideration. Those of us who enjoy video games may find this to be a familiar sentiment, considering games have received similar treatment. The horror genre, like the video game, has a history of having to defend its own existence, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1818 to Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in 1974. However, even in its earliest days (in both literature and film) when it was viewed as a cheap, throwaway genre, people kept coming back for more.

There are many reasons to enjoy horror. The slow burn of suspense. Its inclination toward mystery. The release of pent-up stress. But one signature feature is perhaps celebrated more than any other: the monster. Let’s take a look at how the monsters of our favorite nightmares are put together.

Lethality and Impurity

Philosopher and film theorist Noël Carroll deeply explores monstrosity in his 1990 work The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart. In it, he covers several aspects of the monster. He writes: “Horrific monsters are threatening...This can be satisfied by making the monster lethal.” For me, the go-to monster when thinking of pure lethality is the shark from Jaws. There’s no curse, no interdimensional portal, no transformative virus. Just a big shark, hungry and looming. One of the oldest purely lethal monsters we see in gaming is in 1982’s 3D Monster Maze, which features a T-rex that hunts the player. Again, no particular creepiness. Just pure danger. Some even refer to 3D Monster Maze as the first survival horror game.

Often, however, monsters operate at more than just the physical level, as Carroll continues: “The monster may also be threatening psychologically, morally, or socially.” A psychologically threatening monster might damage one’s sense of identity, like a doppelganger or a possessing spirit. A morally threatening monster might usher in a desire to do evil, like a werewolf or a mad scientist. A socially threatening monster could, as Carroll puts it, “advance an alternative society,” as we might see with cults (Silent Hill) or otherworldly invaders (Half-Life 2). Many monsters fulfill all four of these threat categories. They are physically lethal, psychologically harmful, morally decaying, and socially disruptive, as we see with a figure like the original Dracula.

Carroll adds that on top of being threatening, monsters can also be impure: “Impurity involves a conflict between two or more standing cultural categories.” If a monster combines what we might normally consider to be mutually exclusive qualities, it might be considered impure. Perhaps the most common example is Living + Dead (zombies, ghosts, vampires, etc). Other examples include impure “fusions,” like the werewolf (human + wolf) and many entities in Lovecraft (and Lovecraft-inspired) works, such as The Sinking City and Bloodborne (squid+insect etc).

We might think of these impure monsters as violations of the natural order. However, there is a similar angle worth discussing—one not all that different from the ideas we’ve covered so far, but with an added dimension to them.

The Uncanny

In his 1919 essay titled “The Uncanny,” Sigmund Freud writes:

“...the uncanny is that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar...the German word ‘unheimlich’ is obviously the opposite of ‘heimlich’ [‘homely’], ‘heimlisch’ [‘native’] — the opposite of what is familiar; and we are tempted to conclude that what is ‘uncanny’ is frightening precisely because it is not known and familiar.”

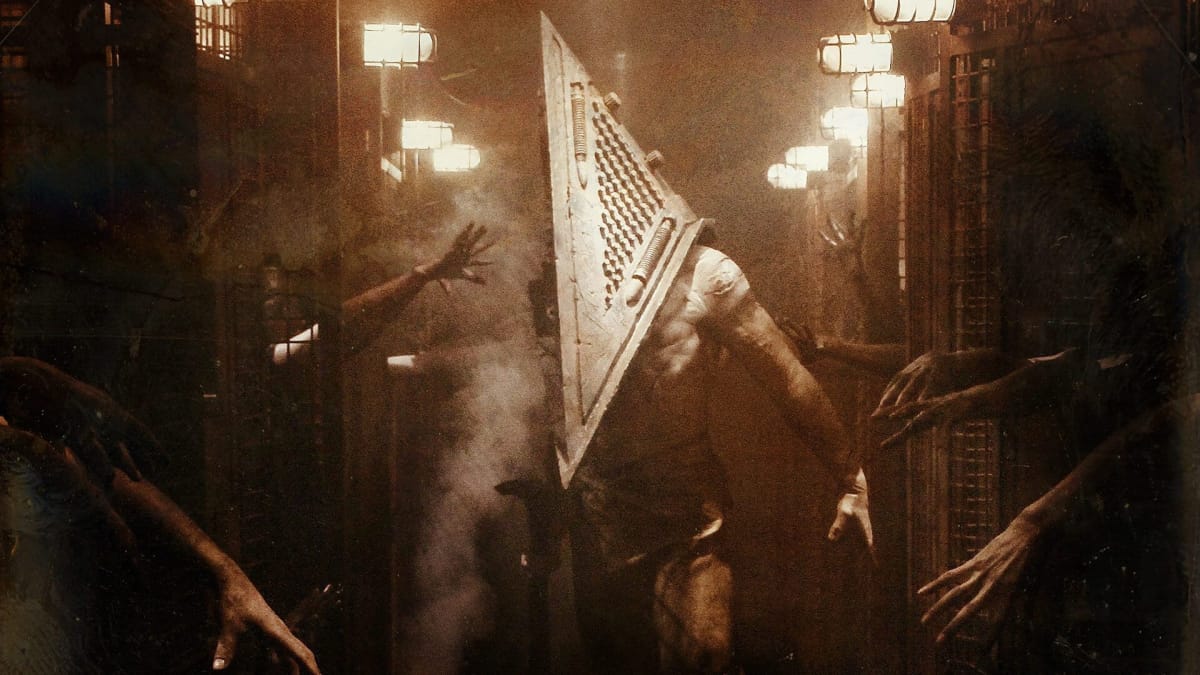

In other words, the uncanny is that which is frightening because it is, in part, familiar, but at the same time unfamiliar. This contrast creates a kind of dissonance that’s eerie or disconcerting. Uncanniness can come across at the level of physical form, as with the Pale Man featured above, who looks so inhuman only because he looks so human. It can also take place at the psychological level. Clowns and dolls are supposed to bring children joy, so to see them rendered as threatening (It, Toy Story) can be frightening, especially for children. Doctors are supposed to heal, so a killer doctor (Outlast) is disconcerting.

We’ve looked at how monsters are constructed in general, but what about video games, in particular?

Game Over

In interactive narratives, lethality means more than just a threat to a character’s life. Often, it means game over. Whether the monster is an eldritch nightmare or a yeti in a cave, death means returning to the last checkpoint. It’s an added consequence that brings another dimension to the the threats we encounter in-game. This is why, for many of us, some of the most terrifying enemies are the ones that kill us instantly. I still get nervous thinking about the chainsaw enemies in Resident Evil 4. Others might shiver at the headcrab-infested Ravenholm from Half-Life 2. Similarly, in games that feature combat, some of the most frightening enemies are those that, for the most part, can’t be killed. This includes figures like Resident Evil 2’s Mr. X, the ghosts of Silent Hill 4, and regenerators (Resident Evil 4 and Dead Space).

We see plenty of other forms of monstrosity amplified in gaming, as well. The most notorious area of Condemned: Criminal Origins (2005), Bart’s Department Store, features mannequins that appear to move around, made all the more frightening by the inclusion of enemies posing among them. Mannequins are undoubtedly uncanny, considering their near-human appearance, and they operate at a psychologically threatening level that points toward the vulnerability of the protagonist’s mental state. However, because a player is in control, the inclusion of shifting, human-like bodies is especially impactful. A player might waste ammo on a harmless mannequin, might question if a given figure is exactly where they’ve last seen it, and may even try to smash every humanoid shape they come across. The uncanniness and the mind games affect how the player navigates the level, creating a much more memorable experience than that of a film scene with a similar premise.

Of course, not everyone shares the same fears. I’m much more afraid while playing horror games than I am while watching horror films. For me, the added responsibility of playing makes it much more frightening, whereas the passive nature of film let’s me dissociate from the situation. For some, however, the agency of a game helps them to feel in control, while films leave them feeling powerless. Everyone’s different. We all have our own set of fears.

What are your favorite monsters, in and out of gaming? How are they threatening? Are they Impure? Uncanny? Share what you’re afraid of below.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net