Molten Core. Blackrock Spire. Ahn'Qiraj. If you're a World of Warcraft player, especially since its launch 15 years ago, those names bring back a lot of memories. Some painful memories of your party or raid wiping for hours on end, perhaps. Others are fond memories of a bygone era. Thankfully, with World of Warcraft Classic's recent launch, you can relive the good times like it's 2004.

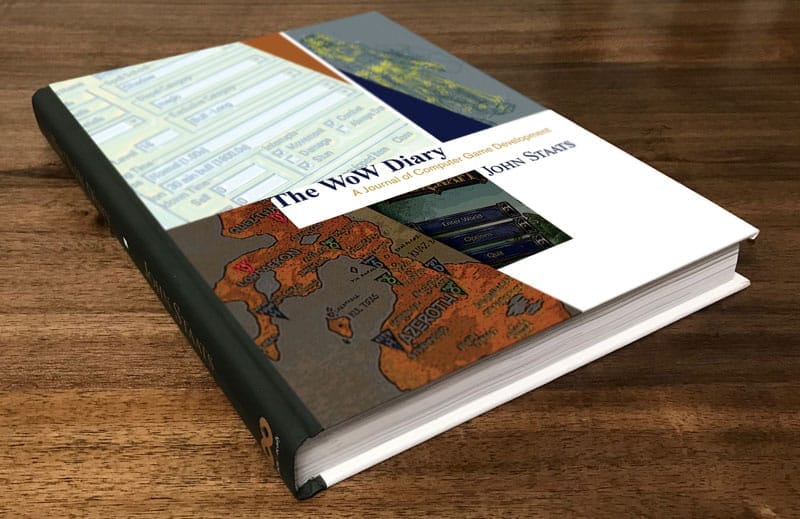

The man behind many dungeons and raids from the original World of Warcraft, in addition to the previously mentioned ones, is John Staats. Although no longer working at Blizzard Entertainment, Staats is credited as having built some—if not most—of World of Warcraft's cherished dungeons and areas. Recently, Staats published his first book, The WoW Diary, which chronicles the development of World of Warcraft.

We spoke with Staats on the phone about his time at Blizzard and the process of creating a dungeon from start to finish, and he wasn't afraid to tell the truth about his thoughts on dungeons like the Razorfen Downs and the Wailing Caverns.

The Kick-off Behind World of Warcraft

“One of the first things that surprised me when I joined Blizzard is how hard it is to hire level designers," said Staats.

He said that most level designers, if they work on a project they enjoy, are content and won't leave. It was tough for Blizzard to find new level designers for the next big MMO (although the genre itself was in its infancy at the time), but Staats was the man for the job.

He moved across the coast to California to work on dungeons and other areas for Blizzard, which as a former dungeon master for Dungeons & Dragons, is a dream come true. As a person who enjoyed both architecture and experience as a former dungeon master, World of Warcraft was a "nexus of likes" to Staats. As for the team that Blizzard amassed?

“It was a blessing that we had the right programmers. I still think the programming team was the best team that has ever been assembled, at least while we were making that team. They were just—every single one of them was just a rockstar," he said. "They were a department in and of themselves.”

The massively multiplayer online role-playing game genre was barren at the time. Designers like Staats drew inspiration from FPS games, with him citing Quake in particular. The team began with a tool that made everything far too clunky and rigid, with inflexible geometry, as Staats described it. But more importantly, the team looked at EverQuest. The team's aim was not to directly emulate what their potential competitor already does, but to improve upon it. This was the philosophy of Allen Adham, one of the founders of Blizzard Entertainment.

"Allen was our design lead up until the last year of the project," said Staats, "and I remember him saying that, 'World of Warcraft wasn’t going to be revolutionary; it was going to be evolutionary.’”

Building Blocks for WoW's Dungeons

“It would start at the concept phase," said Staats. "We would talk about it to death, because everything took so long to make, that we would have plenty of time to talk about dungeons. Like, we had this concept of this old wild west newbie dungeon for the tauren. And, nobody could figure out like what would it really look like? And, there’s really no strong interior spaces that are iconic for wild west types of adventures.”

Staats said it's particularly hard to do concept sketches for dungeons, because interior spaces and capturing the essence of these areas is just hard to do. Often times, Chris Metzen would help conceptualize ideas for dungeons. Once someone understood his requirements, they would work out "the nuts and bolts" as Metzen dashed to the next meeting. Staats himself would begin sketching with graph paper, once again relying on his experience as a dungeon master.

“If I’m going to invest a few months of my time into this, it’s going to be good," he said.

His job as a level designer is to make the dungeon interesting at every angle the player looks. The design process is long and arduous at times. Level design is much further along in development than monster design and the like, so Staats wouldn't necessarily know what the models of NPCs look like until way down the road. Furthermore, you couldn't test combat so early in development, because high-level spells hadn't been implemented into the build yet.

“It was just an act of faith, walking forward and hoping you don’t fall on your face," said Staats. "And we did fall on our face. Our dungeons were— they turned out to be way too big. Wailing Caverns, I think we should have broken it up into a number of dungeons.”

Once the idea is conceived and a proper layout created, Staats begins by laying down the floors of a dungeon. He was able to stretch the geometry of the floor to create walls. If two different parts of the dungeon weren't connected but were in close proximity to one another, through his program he was able to punch holes in the wall to create a window for players to proceed throughout the dungeon. This method was used in Wailing Caverns in particular, which was essentially a winding path that gave players a different view through a singular room. It was also important to get a feel for the size of the dungeon in relation to your player character.

“It’s a lot of iteration," said Staats. "It’s just lots of tweaking things, and just improving things. Because when you’re working on something for three months, your mind wanders and you’re going to think, ‘Oh, this could be a cool thing over here,’ because you’re kind of bored after a while and just work up stories in your mind to like, even entertain yourself and get through it, and you come up with these interesting ideas, and it just accumulates. It’s like a reef structure, just lots of little ideas on top of another until it becomes its own shape."

Finishing Touches

After Staats was finished laying out his dungeon, and once an artist spiced up these instances with details like foliage, it would sit in a queue. Sometimes months and months would pass while a dungeon was left unattended, until it was time for someone to properly texture the dungeon, add lighting, and the like.

The space of a dungeon is inhabited by monsters. Some developers were tasked with creating a pool of monsters and create varying packs of enemies to be placed throughout the instance. Testing these monsters as well as boss dungeons didn't typically happen within the dungeon itself either—designers would go to where they began building Azeroth from the ground up: Westfall. It was a wide open space where gameplay designers could properly balance out these encounters; that is, unless geometry was essential to the fights themselves, adds Staats.

“Now, that was another mistake that we made, is that we also overspawned our dungeons," Staats said. "So, in addition to overbuilding our dungeons, we also over-spawned them."

One of Staats' first dungeons he made is one he dislikes to this very day, and is one of the only instances he never explored as a player himself: Ahn'Qiraj 40, the legendary raid that put the most hardcore World of Warcraft players' skills to the test. He had no idea how big it was supposed to be while designing it, and was heavily restricted with textures, which made it difficult to individualize rooms of this particular raid.

And Metzen didn’t want to be bothered to come up with different types of monsters, so all I knew was that they were some kind of bug in this area—we didn’t really have any idea what the bugs were going to be—and I just built. And they kept saying bigger, bigger, bigger, and as it turns out, I was building longer, longer longer, where the play spaces were too narrow. Ahn'Qiraj 40 was just such a mess.

Despite memories of Ahn'Qiraj and other difficult delves nagging at Staats' mind, he is happy to hear that players are enjoying World of Warcraft Classic, playing an experience that he had an integral role in creating. With his newly released book, The WoW Diary, you can hear more about his experience with Blizzard during the creation of World of Warcraft.

“The interesting thing about it is that it’s not written by the company," said Staats, "it’s not a PR piece, it’s the straight story. If you want to be a fly on the wall and listen to the game designers argue with the programmers about something, it’s really how you make the sausages. And you never really see a lot of books about any industry, let alone games. I honestly think that what they’ll find most interesting is that it dispels most of the myths about game development that you didn’t even realize that they were a myth.”

While the work Blizzard developers put towards World of Warcraft seemed supernatural, Staats believes his book humanizes things. Take it from the dungeon master himself.

You can purchase John Staats' book, The WoW Diary, on Amazon now. His website is whenitsready.com, where you can find a PDF version of the book.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net