One of the strangest parts of tabletop culture is the preference for game design, the mechanics that more or less make up the bulk of the game experience. For role-playing games, this has become a paramount way to discuss and define what type of game you may enjoy. Increasingly these discussions of preference have grown as the industry expands and has bled over into RPGs in video games as well.

Typically, there are two philosophies employed for tabletop RPGs. The first is abstract rule sets. Abstract rules typically make the gameplay separate from the world. The mechanics recognize that you are in a game, making the numbers and rules governing the game somewhat arbitrary to the design; that is, fluid in their presentation and more concerned with keeping the mechanics simpler and less defined. Games such as Fate and Apocalypse World tend to fit this category.

The other philosophy is called concrete rule sets. The complete opposite of abstract, concrete sets use a more rigid system to track statistics and simulate the real world. The mechanics are tied to the world itself, meaning the plausibility of the game is interpreted through them. This tends to lead to what is known as “crunch” in systems, heavy rulesets, and a lot of statistics to accurately portray what occurs in the world. Shadowrun and Pathfinder are often cited as good examples of a more concrete system.

Of course, it should be noted that some aspects of both rule sets overlap. Hitpoints, for example, are an abstract system designed to track the overall wellness of a character and are typically found in almost all games regardless of which philosophy you fall under. What could make hitpoints more concrete by design would be sectional damage on characters; how much damage has your arms or legs taken in combat vs. your whole body, or how constitution determines the amount of hitpoints you gain upon leveling up. This is just one example of this overlap, so the two philosophies are often combined into one to create a system.

For tabletop games, it makes distinctions a bit more complex; some see the GURPS system for example to be extremely concrete, but due to its modular nature it can be used abstractly at the same time. Other games, such as Dungeons and Dragons, have gone through five different systems, each offering their own focus on either abstract or concrete design. Video games, however, are a bit different. While we see elements of both philosophies in our games, many of these traits tend to be regulated to a specific philosophy despite the blending of them.

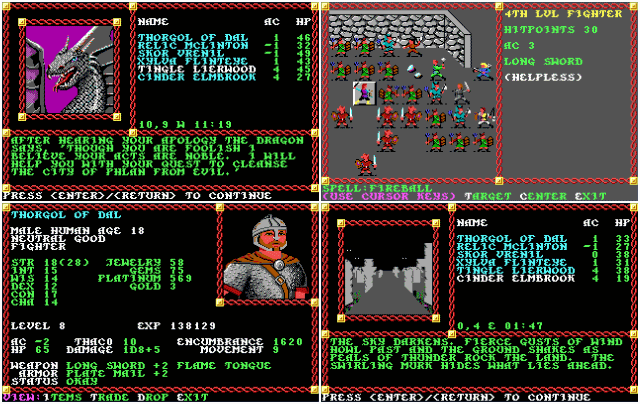

Modern games in particular are scrutinized the most for this but the majority often combine concrete rules and abstract mechanics, in spite of games being regulated in the minds of role-playing gamers. Older games tended to be more clear-cut than today. The CRPG games of the 1980s and 1990s were heavily concrete in their mechanics, often simulating aspects such as weight, weapon proficiency, class and spells, traps, and agility. By design, many of these games followed very closely the Dungeons and Dragons rulesets of the day, which were very concrete in their own fashion. Many of these games were also dungeon crawlers and early MUDs, built from the ground up based on a ruleset that already existed.

The prevalence of the Dungeons and Dragons ruleset was paramount to the success of many early CRPG games. The SSI Goldbox series for example was only possible due to SSI acquiring the Advanced Dungeons and Dragons license from TSR Inc. back in 1988. SSI would release 14 games based on the rulesets of TSR from 1988 to 1993. The first game, Pool of Radiance, would be the emblematic showcase of most of the SSI titles, offering players a complete Advanced Dungeons and Dragons experience on their computer, right down to the experience points.

As noted in previous articles, however, by the mid-1990s the CRPG market began to falter, primarily through bad game design, staleness of the overall genre, and poor coding by the game developers. Titles like Fallout and Bladur’s Gate rescued the CRPG market in the late 1990s, offering fresher takes on that concrete design than ever before and showing that even today, these types of games can still be quite popular. Fallout continues to use both the VATS and SPECIAL systems in combat and character creation. Pillars of Eternity by inXile created their own ruleset, but use the ruleset in a way that offers more simulation and concrete statistic tracking as the primary feature of the game. So games focused on concrete mechanics are not going anywhere.

Abstract design has always been present, however, even in concrete games. The difference is the abstract design is taken for granted in older titles. CPRG games, because of their rule-heavy mechanics and general statistics, often handwaved some of the more abstract elements of their games as they were not the focus of the design. For console role-playing games, the abstract design took root in most instances, offering a “gameplay first” mentality in titles such as Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy. What makes these games abstract is how they treat the game mechanics.

There are statistics mapped to weapons, armor, points, and magic points, and there is a governing, concrete rule behind those points—certain characters will always have more health or more magic based on their profession or character traits. What makes this abstract is that the player has little control over it; it is pre-determined instead of modular. A game like Pool of Radiance allows the player to change their statistics and party makeup quite liberally, and the crunch in the ruleset allows for multiple character builds. A game like Chrono Trigger provides that for the player, making the creation process abstract by design so players can focus on the characters and the story as it is presented. It is more than just character creation. Weapon statistics, abilities, even positioning, and strengths and weaknesses, tend to follow this pattern.

Many games today don’t even offer concrete statistics, instead giving percentages to the player that abstractly tell you your progress in the game. An increase of weapon damage by 50% has replaced the 2-point increase in damage, despite often having the same effect in a video game.

Some games however fail to use abstract design to their advantage. Dead Island, for example, offers weapon and statistic increases as hard numbers, but the world levels up with the player, meaning the increases become completely moot to the game's own design. It becomes abstract in that case because the statistics rarely matter in Dead Island; what matters is you find a better weapon to beat up zombies with. MMOs also have this abstract design in them; the increasing numbers and strength of your character become secondary as the number of statistics is often tied to the rarity of your gear—not your character or their level.

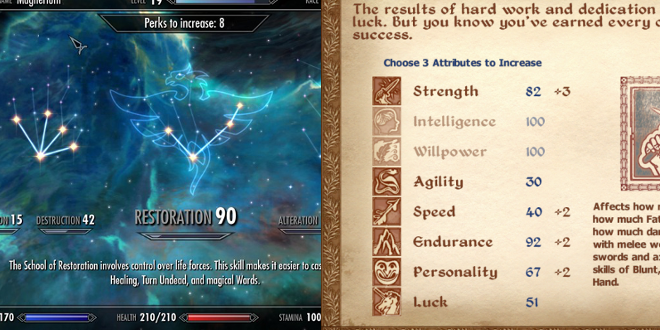

It seems that the two design philosophies are often found on opposite ends of the spectrum. Many also find fault with one design philosophy over the other, but much like how role-playing games are beginning to shed their “WRPG/JRPG” labels, a similar change has been occurring in the past decade regarding how these philosophies of design are implemented. Take, for example, the Elder Scrolls series. Originally starting with a very concrete ruleset, over time the ruleset became more and more abstract by design. The amount of skills and abilities in Oblivion changed over in Skyrim is emblematic of this change, for example. In Oblivion, you had character attributes and several abilities the character would be proficient in, creating a more concrete rule set that follows the paradigm of the previous iterations of the Elder Scrolls series. Skryim eliminated these attributes altogether, instead focusing on customization of primary skill sets for your character with three governing, abstract attributes in health, magicka, and stamina. Many often say this streamlining of Elder Scrolls is endemic to “dumbing down” role-playing games, but in truth, the complexity is just shown more abstractly.

Skyrim still encourages experimentation in character builds, and direct access to different skills, coupled with the method of leveling them up being retained between Oblivion, allows players to generate any character class they wish on the fly. The charge of “dumbing down” role-playing games is often thrown around when a game system becomes more abstract, but for many of these games, this is done due to the accessibility and popularity that abstract mechanics can have in the game system. It does not eliminate complexity, but it does create a barrier between the desire for “simulation” and trackable statistics. For example, Dragon Age: Inquisition received some criticism for having their warrior class doing “unrealistic” things in combat, with many arguing it was too abstract in a game that was supposed to be real and offered no statistical differences between abilities and their use.

The issue at hand stems partially from personal preference of what design philosophy we prefer and partially from how games are now made. Modern design philosophy often constitutes three primary categories: the mechanics, the dynamics, and the aesthetics, or MDA. Each of these categories, as explained by the paper A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research, written by designers Robin Hunicke, Mark LeBlanc, and Robert Zubek, outlines these three categories as to how they can shape the player's experience. The mechanics are the specific rules of the game, the dynamics are mechanics in action, what the player interacts with, and the aesthetics refer to the experience the player has. All of these categories are less scientific to actual game design but are seen as the desired philosophical “goal” of making a game.

The MDA paradigm is now often tailored to how games operate. For example, a game such as Skyrim has various weapons that can be used by characters based on their class. In Skyrim, a character can use a one-handed sword to fight an enemy; the sword has an animation, and the fight against the enemy is the base mechanic. The dynamics of the fight include how fast or slow the sword swing is, how much damage the enemy takes, and the aesthetic is how frantic, or in the case of Skryim, visceral the combat becomes in the process. In one short moment, we see the MDA paradigm in action; the mechanics of the fight lead to the fight being dynamic because of the elements involved in the fight, which lead to an aesthetically good or bad response by the player. The MDA paradigm arguably opens the doors to much more outside of concrete systems, which is possibly one of the reasons why many role-playing games often employ more abstract elements.

However, even a series like Dragon Age, or other contemporary games, tend to combine the two philosophies together. Inquisition removed its emphasis on character statistics but continued to reference them through weapons and armor, especially when crafting them. So while the Inquisition removed some of the concrete statistics that governed the “realism” of the world in favor of abstract mechanics, it retained many of those statistics to enhance the gameplay beyond the abstract, offering a mix of the two philosophies, however slight, to the player. This also allows the MDA paradigm to continue; the enjoyment a player can get by acquiring a rare weapon with a high DPS, or a power that gives the player satisfaction with their character build is part of the design philosophy the developers employed when making the game. They wanted players to feel this way when playing their game.

Role-playing fans will no doubt categorize games based on these philosophies, consciously or sub-consciously—players categorize games based on preferences and their design. Yet more and more we see the philosophy of design shift into something different. The MDA paradigm can be used in pretty much any game, from Pool of Radiance to Skyrim; the philosophies behind the design tell us the story of what type of game the developers wanted to make. This gives us a new perspective on the philosophy of game design, especially regarding the diversity found in rule sets in role-playing games. Developers can make a very crunchy or abstract system for their games without losing complexity or flexibility if done correctly. The best modern role-playing games walk this tightrope of design philosophies carefully, and we see a mix of concrete rule sets and abstract design employed in many successful RPGs today, such as The Witcher, Dragon Age, and Fallout. Through it all though, the preference of the player becomes the deciding factor in their personal enjoyment of the game's design.

The philosophies just become a tool, a way for developers to quantify their design choices and to help them push for a specific goal in developing a game. It helps developers answer simple questions about the design while offering rule sets that can always continue to evolve and change. Such diversity just contributes further to the flexibility of the role-playing game genre itself—a philosophy I doubt anyone would argue. With this, the importance of the game's design cannot be understated, as it influences the type of game and experience the player can have. RPG fans may differ on how we approach said philosophies, but one thing is for certain, we wouldn’t have as many role-playing games without these philosophies at the core of the design process.

This post was originally published in 2015 as a part of our Playing Roles series. It's been republished to have better formatting.

Have a tip, or want to point out something we missed? Leave a Comment or e-mail us at tips@techraptor.net